Submarine hunt at Muskö Naval Base south of Stockholm on 5 October 1982.The submarine incidents in the 1980s and especially the events in Hårsfjärden near Muskö Naval Base in 1982 were of enormous importance for the Swedes' perception of a threat from Moscow. Sweden was changed from one year to the next. Up to 1980, 25-30% of the Swedes had perceived the Soviet Union as a direct threat or hostile to Sweden. Three years later, in 1983, this figure had been changed to 83%. Sweden had become a different country. The whole public opinion changed. The Russian threat dominated Sweden. The Swedish Social Democratic Party, now in government, had to go on the defensive.

This article will study a specific incident: what happened when the Swedish fast attack craft Väktaren dropped a depth charge at 14:40 on 5 October 1982. There is no definitive evidence, but a large number of sources claim that a small underwater vehicle was sunk or was seriously damaged at this moment. Statements from both Swedish and American decision-makers, both civilians and military, point in this direction. A former CIA Deputy Director for Intelligence and a former US Secretary of the Navy spoke of this incident as an “Underwater U-2,” meaning that this event may have had the same significance as the downing of the American U-2 aircraft over the Soviet Union in May 1960, but nothing became public about the Swedish incident.

Many of the sources to this article are not to be found on internet and many of them refer to documents in Swedish and other countries archives and to books and interviews not to be found on internet. To make it possible to find original sources, I have made a link to an earlier Norwegian version of this article (“40 år siden «U-2-episoden under vann»”), which has regular footnotes and was published in 2022. I will add this link to every chapter.

In Part I of this article, I start with a first section that brings up the U-2 incident of 1960 and I describe the significance of this event. The second section presents some statements about a damaged or sunken midget submarine made by senior officials. The third section discusses Swedish documents about this very incident in 1982: the naval base's war diary, the Chief of Defense’s diary and later Chief of Navy Dick Börjesson's report about tracks on the seafloor. I record interviews with several people on the military and civilian side who were directly involved in the incident, and not only with Swedes, but also with Americans and Norwegians. In the fourth section, I present information from a number of conversations with officers and civilians from US intelligence and from the US Navy, but also interviews with key figures conducted by Dirk Pohlmann for the German television channel ZDF and the German-French channel ARTE.

In Part II I continue with a fifth section, where I discuss possible scenarios for vessels that may have participated in the operation. I discuss British and West German submarines and Italian mini-submarines under US or British command. This section is partly based on American literature, and partly on conversations with centrally located people from the United States, Great Britain, Germany, Norway and Sweden, not least with the former head of Naval Intelligence Europe, Robert Bathurst, with whom I worked together with for ten years. The sixth section is based on documents from Sweden’s official Cold War History report 1969-89 (2002), from the then navy chief, and from the former head of intelligence written for Prime Minister Ingvar Carlsson, but also from books by Ingvar Carlsson himself and by his Defense Minister Thage G. Peterson.

In Part III I continue with a seventh section that brings up details about the Swedish system based on conversations with Navy Intelligence professionals like Robert Bathurst and with his colleague Bobby Inman. While Bathurst in the mid-1960s was assistant attaché in Moscow, Inman was assistant attaché in Stockholm. Inman was then Director of Naval Intelligence, Deputy Director for Defense Intelligence Agency, Director of the National Security Agency and Deputy Director of Central Intelligence (DDCI). He was also President George H.W. Bush's closest adviser on intelligence. The chapter is based in part on information from a former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and from officers of Naval Intelligence. An eighth section brings up some information from key figures in the CIA and from Admiral James "Ace" Lyons, who in 1981-83 was Commander of the US Second Fleet, and in 1983-85 Deputy Chief of Naval Operations. He was contacted directly by Director of Central Intelligence William Casey and said: “it was my staff”, who did it. This chapter is followed by a discussion about the sources.

U-2 aircraft at unknown airport in the 1960s.1. U-2 aircraft over the Soviet Union in 1960

The downing of the U-2 aircraft on May 1, 1960, was perhaps the biggest event in the world that year. It was a disaster for the United States. A CIA’s U-2 surveillance aircraft was shot down over the central Soviet Union near the Ural Mountains at Sverdlovsk, now Yekaterinburg (2500 km north from Turkey). The plane, which came from Peshawar in Pakistan, was on its way to Bodø in Norway. It flew very high and took extremely good photographs. It was supposed to cover a large part of the Soviet Union and take pictures of many military installations. The plane flew too high for the Russians to attack it, but now it was shot down. The explosion from a missile occurred just behind the plane, as if it had been an accident that it was shot down. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev protested sharply. The United States, which at first had no idea what the Russians knew, immediately followed its cover story, which is always planned in advance. The US claimed that the plane came from Adana in Turkey. It had run into trouble and had disappeared north of Turkey. The aircraft was supposedly tasked with studying air movements. The pilot reportedly lost oxygen supply and had reported that he could not land in Adana. It was suspected that he might have fainted. CIA-chief Allen Dulles, the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) had given "absolutely categorical" guarantees to President Dwight Eisenhower that the pilot would never be able to survive a crash and that the Russians would never be able to shoot down the plane at that altitude. The United States claimed that it had not deliberately violated Soviet territory (Bamford, 2002; Brugioni, 2010; Burrows, 2001).

However, it turned out that the Soviets had succeeded in shooting down the U-2 aircraft, and that the pilot Gary Powers had survived and been captured by the Russians. The Soviets had been able to develop the film and they told that the pictures were extremely good. Pictures had been taken of important military installations. Now the Americans had to acknowledge that its task was espionage over the central Soviet Union. It was the biggest diplomatic disaster for the United States that year. Khrushchev could make fun of all US lies. The Americans had lied to the media and lied at the United Nations. Eisenhower wanted to fire CIA Director Allen Dulles, but he couldn’t. It would give his own administration the impression that he himself was not informed, which many knew he was, and it would give the Russians the impression that he himself had no control over the CIA or of his own administration. Eisenhower wrote that Khrushchev might then be able to disregard his own arguments. Khrushchev could say that it didn’t matter what promises Eisenhower gave, because he was not in charge anyway.

The same problem arose in Norway after the U-2 incident. Despite the fact that many in Bodø and in Norwegian intelligence knew about the U-2 aircraft, it was unclear what Prime Minister Einar Gerhardsen knew, and what his Foreign Minister Halvard Lange knew. Gerhardsen said that they had informed him about allied reconnaissance aircraft that had landed at Bodø Airport for short visits, but he knew nothing about the landing of the U-2. Lange told Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko that also he had not been informed. “All the worse”, Gromyko replied, according to Lange's close adviser Einar Ansteensen. That is, if the prime minister and foreign minister knew nothing, it means that the Americans could do whatever they wanted on Norwegian territory. The government did not have control over its own military forces. How could the Russians trust the prime minister’s words, if he did not know what his own staff was doing?

A Soviet lieutenant general, Vladimir Cheremnykh, whom we invited to the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) in 1994, had been involved in shooting down the U-2 aircraft. It was important to his career. In 1976-86, as the first deputy chief of staff of the Leningrad Military District, he was responsible for military planning for Northern Europe except for a year 1980-81 when he was commander-in-chief of Soviet forces in Afghanistan. The U-2 incident was one of the biggest intelligence scandals of the Cold War. However, there was one apparently equally serious incident in Sweden, at the Muskö Naval Base in 1982. And what I learned from Cheremnykh was that this incident, “a sunken mini-submarine”, was not Soviet.

US Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger presenting President Ronald Reagan with the first copy of Defense Department's popular publication, "Soviet Military Power" 1983 (Wikipedia; Public Domain). Defense Department was able to present the Soviet Union as an aggressive power and the use of Western submarines described as Soviet submarines totally changed the perceptions of a Soviet threat, not only in Sweden but in Europe as a whole.2. Statements by senior officials about a damaged midget submarine

In June 1993, PRIO held a conference at Rjukan on nuclear weapons and international politics. I had long conversations with James Schlesinger, President Richard Nixon’s CIA Director and Secretary of Defense (1973-76). I had a lunch with him and, during our car journey back to Oslo, he confirmed that there had been a damaged submarine at Muskö Naval Base, a Western submarine under US command. But he “didn’t remember the details”, he said. He wouldn’t say more. A person who, because of his position, had listened to a conversation between two English-speaking ambassadors could tell the same thing. And in 1999, Einar Ansteensen said almost the same thing to me during a conversation I had with him in December 1999 at the home of Bernt Bull, the advisor to former Minister of Foreign Affairs Knut Frydenlund. Ansteensen had not only been Lange's closest advisor, but he had also been heading the Political Section and the Policy Planning Staff at the Norwegian Foreign Ministry for 15 years. He had been a mentor to foreign ministers Knut Frydenlund and Thorvald Stoltenberg. Ansteensen had been at dinner with the US naval attaché in Stockholm during the submarine hunt in 1982 and was told that the Swedes had accidentally sunk or seriously damaged a small submarine under US command. “It was a sad story”, he said. He had only told Norway's Chief of Defense, Sven Hauge about it, but he had not informed Hauge’s Swedish counterpart General Lennart Ljung and not Prime Minister Olof Palme, whom he knew quite well. He wouldn’t say more. It was obviously very sensitive.

When I was a civilian expert in Sweden's official Submarine Inquiry 2000-2001, I told Ambassador Rolf Ekéus who headed the Inquiry, what Ansteensen had said. Ekéus knew Ansteensen, and what he knew was obviously important. The Inquiry had been created after President Ronald Reagan’s Secretary of Defense, Caspar Weinberger (1981-87), had said, in a lengthy interview on Swedish television (SVT) in March 2000, that the United States had regularly and frequently operated Western submarines in Swedish waters to “test Swedish readiness”. A month later, in another SVT interview, British Navy Minister Keith Speed had said the same. He told about “penetration dive exercises. Can submarines actually get in and almost surface in the Stockholm harbor? Not quite, but that sort of thing. How far could we get without you being aware of it.” Both Weinberger and Speed said that those operations were launched after “Navy-to-Navy consultations”. For Britain, it was the British chief of defence staff or the flag officer submarines who consulted their Swedish counterpart. We have reason to believe that the mini-sub at Muskö 1982 was not a Soviet one, but a submarine used in such a tests that Weinberger and Speed had talked about.

Each year, the directors of U.S. Naval Intelligence, John Butts (1982-85), William Studeman (1985-88), and Thomas Brooks (1988-91) gave a briefing on Soviet naval activity and threat to the Western countries, to the Armed Services Committee of the House of Representatives, but they never talked about Soviet intrusions into Swedish waters. These intrusions didn't exist. If they had confidence in the Swedish reports, they would have said so. In March 1984, the Armed Services Committee asked Director Naval Intelligence Rear Admiral Butts, along with Weinberger's Secretary of the Navy, John Lehman, about the submarines in Sweden 1982-83. Butts said that the submarine that ran aground at Karlskrona in 1981 was a “genuine” Soviet submarine, but the paragraph about the submarines at Muskö 1982 is still classified. This means that these submarines were hardly genuine Soviet submarines. There was no reason to keep such information secret, and it has still not been possible to declassify. Shortly after this meeting, however, there were leaks from senior officers. They told ABC “World News Tonight” (21 March 1984) that the US Navy had operated submarines also in the waters of friendly countries, while deploying hydrophones and while “gauging a country’s ability to detect intruders”. Swedish criticism of the United States had apparently made Sweden a target of such operations. Ansteensen said the Americans had operated submarines in Swedish waters, but only up to a certain latitude so as not to disturb the Finns. Ekéus and I agreed that I should talk to Ansteensen as soon as I was back in Oslo, but when I arrived in Oslo he had just passed away. At the memorial service after the funeral (17 April 2001), I sat next to Ambassador Arne Arnesen. When I told him about the Inquiry and what Ansteensen had said, Arnesen said cautiously: “Are the Swedes mature enough for that?” It was obviously sensitive. I also had regular conversations with then Prime Minister Kåre Willoch, who said that he could neither confirm nor deny what Ansteensen had said, but he also added: “One could trust that what Ansteensen said was correct.”

The Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter gives a dramatic description of the submarine hunt in October 1982. The headlines: “The hunt for the submarine” and “The submarine is trying to escape”.3. An underwater U-2 episode in the Stockholm archipelago 1982

I had a special reason to take an interest in this event. In 1985, I had a contact with a Swedish diver, who had told that during the submarine hunt at Muskö in 1982, he had dived down to a damaged mini-sub or rather a midget and attached a wire to it. They had first observed a small “black hill” (later described as a “whaleback”) on the surface. It had been watched for a few minutes until 2:15 PM (according to the Naval Base War Diary). A helicopter made contact with it. A Swedish fast attack craft Väktaren dropped one depth charge on it. By accident, it had hit and sunk the midget, the diver said. A mini-sub may had been “damaged from a depth charge on one occasion”, wrote the 1983 Submarine Defence Commission in its report. According to the Naval Base War Diary, there was only once a fast attack craft dropped only one depth charge: Väktaren at 2:40 PM on 5 October. It was given target information by helicopter 71. The timing of the "damaged mini-sub" was confirmed for the Submarine Inquiry 2001 by the intelligence chief of the Naval Base 1982, Mauritz Carlsson. The Chief of the Navy Per Rudberg (1978-84) said in 1983 that a mini-sub had been damaged. At 2:42 PM, two minutes after the detonation, the helicopter Y71 reported: something on the surface. At 2:50 PM, Y71 returns to base. According to a military doctor at the Naval Base, the helicopter division came with an American diver, who had made a free ascent. He survived. They called him “Ohio”. They asked him where he came from, but he didn't say anything. He just pointed straight down. A U.S. Embassy car arrived after an hour and took care of the diver. It was something of an “underwater U-2”. As in 1960, the pilot had survived and been taken care of. I talked to the military doctor a couple of times. He had contacted me after my book Hårsfjärden in 2001. He died shortly afterwards.

At 3:44 PM, all traffic in the Hårsfjärden area is stopped. At 4:10 PM, the submarine salvage vessel Belos is ordered up from Karlskrona (a distance of 400 km). At 5:40 PM, the Unmanned Underwater Vehicle Sjöugglan (to take photos under the water) is placed at the Naval Base's disposal. At 6.10 PM, the vessel Urd (for salvage of torpedoes) is ordered to the position of the detonation. All reports from Urd are still classified. The helicopter Y69 patrols the beach at Märsgarn east of the detonation for two hours as if one were worried that something or someone would be washed up on land. The War Diary writes: “11.17 PM: all divers have returned” All naval vessels in the area were ordered to shut down their engines. It was completely silent all night, as if one had mourned someone. The following day, Vice Admiral Rudberg went to the helicopter division to speak to the staff. Something serious had happened.

The Chief of Staff for Muskö, Lars-Erik Hoff, could not tell me what had happened, but he told me that Dagens Nyheter's editor-in-chief, Christina Jutterström, had called him and said that she had absolutely certain information that a small submarine had been damaged. She wanted the case confirmed. The captain of the salvage ship Belos, Björn Mohlin, said that she had called him as well, but Belos had arrived at Muskö a day later. He didn't know anything, he said. When I spoke to Jutterström, she would not reveal her source. She had the “duty” to “keep quiet”, she wrote. The Navy Press Officer, Sven Carlsson, later said that Chief of Defense Staff, Vice Admiral Bror Stefenson, had flown down to Berga Naval College at Hårsfjärden to hold a first press conference for the global mass media, at 6 PM. All major international tv-channels were present these days and up to 500 journalists. Carlsson briefed Stefenson and the Commander of Berga, Naval College Commodore Christer Söderhjelm. It may have been an hour before the press conference, perhaps two hours after the mini-sub had been damaged or sunk. It was very secret. Carlsson was not informed. After Carlsson’s briefing, Stefenson said he was going to bring up something else instead. Carlsson was astonished: What would that be? he told me. Söderhjelm said: “I think the admiral should listen to Sven Calle [Carlsson].” But when Stefenson was holding his press conference, he couldn't say anything about what had happened. He started talking about himself. He hadn’t listened to Sven Calle’s briefing. He hadn't made any notes. Someone must, just before the press conference, have given him strict orders not to say what he intended to say. Sven Calle took over the press conference from the admiral. Stefenson may not have known until later what nationality the mini-sub had. The head of Stockholm Coastal Defense forces, Brigadier-General Lars Hansson said in an interview with Aftonbladet the next day that it may have been a Soviet submarine or perhaps “a NATO submarine that wanted to test us”. Stefenson asked Hansson to come to his office: “There are rumors about a NATO submarine. These are rumors, we must immediately and forcefully deny,” he said.

The Navy’s main report on tracks and objects on the sea floor after the submarine hunt in 1982 is now largely declassified (many attachments are still classified). Divers had found tracks on the bottom. It looked as if there had been a tracked vehicle that had gone on bottom off Näsudden, where Väktaren had detonated a depth charge, but also at Mälsten. A short paragraph (12 lines) in the report is about two wrecks on the seafloor, however, now, after 40 years, this paragraph is still classified (sonar images of these two wrecks can be found in attachments that are still partly classified). I went to a higher court to get these lines and some attachments declassified, but it wasn't possible. One wreck was 16 meters long, while others less than 10 meters. That the Navy had dived on these wrecks was declassified in 2001 but was reclassified in 2008. Why? In addition to the original document written by later Chief of Navy Vice Admiral Dick Börjesson, there were two copies. The Report and one copy were given to the Chief of Navy Vice Admiral Per Rudberg, while the other copy went to the Chief of the Naval Base, Rear Admiral Christer Kierkegaard. One has to ask why one still keeps this information secret. These were also the two Swedish admirals that had briefed and escorted Defense Secretary Weinberger during his 5-days’ visit to Sweden almost exact one year earlier.

1984-85, I talked with an officer who knew the diver, who had attached a wire to the small submarine. It was difficult to arrange a joint meeting, so I called the diver on a Sunday evening, where he lived south of central Stockholm. He agreed to meet me on Tuesday morning less than two days later. He had a day off and was going to wash clothes. I got his address and door code. I gave him my phone number if something would happen. He called the following day and said it wasn't possible to meet. He had been transferred to a town in North Sweden several hundred kilometers away. I called him in the North after a week. He then said that he could not talk about it. He had left his apartment and girlfriend in Stockholm on one day’s notice. He never came back. When I was a civilian expert in the Submarine Inquiry in 2001, 15 years later, I called him in North Sweden from our office at the Ministry of Defence. He then said that he expected me to call (after not having talked to me for 15 years). Someone, who knew that I was in the Inquiry, had warned him. He said that he had not been at Muskö at the time, but in Karlskrona. Others told that he had been at Muskö. It was clear that he didn’t want to say anything more.

One might ask: how credible are such sources? Why should we believe a diver, a doctor or an officer who makes claims that are not compatible with the official version? But these sources were not alone in talking about a damaged mini-sub. Chief of Navy Per Rudberg did it. The documents point in the same direction. Something serious had happened. The Swedish Navy needed to show something concrete. One claimed that the submarines were from the Soviet Union, but the Navy needed to present evidence. If there had been a sunken Soviet mini-sub, they could have picked it up and shown it to the world. A sunken Soviet mini-sub makes no sense. When Einar Ansteensen in 1999 said that the damaged submarine had been under American command, and when others said that one picked up a US Navy diver, everything became much easier to understand. Now, it was possible to understand why the Navy couldn’t say anything about what had happened. When Defense Secretary Weinberger and British Navy Minister Keith Speed in 2000 said that the US and the British regularly and frequently had operated submarines in Swedish waters, this was confirmation of what several of us already knew, but which people were involved?

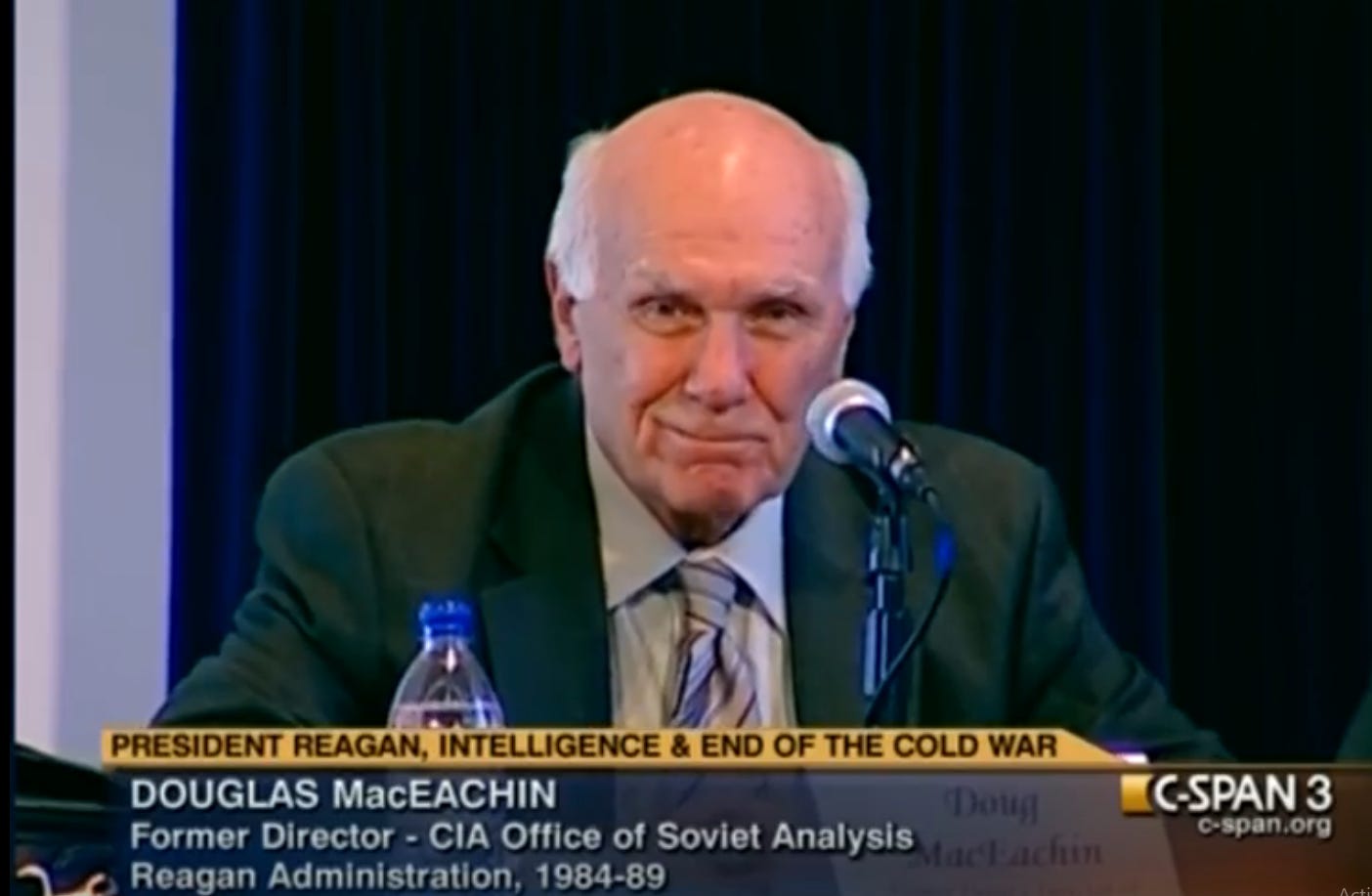

Screenshot, former CIA Deputy Director for Intelligence (DDI), Douglas MacEachin (heading CIA Soviet Analysis 1984-89) speaking on “Intelligence Used to End the Cold War” at the Reagan Library 2011, he was speaking together with former Deputy Director for Central Intelligence Admiral Bobby Ray Inman.4. A top secret "Underwater U-2"

In April 2002, I presented my early English manuscript on Western submarine operations in Swedish waters to the international group of historians at the Norwegian Nobel Institute. The manuscript was developed into a book on “US and British submarine deception in the 1980s”. At the Nobel Institute, I put forward a lot of information that all pointed to Western activity, and one of the historians was more interested in this topic than the others: Benjamin Fischer. He had worked for the CIA for up to 30 years. He had later held the position as the CIA Chief Historian. In June 2002, the Nobel Institute had a symposium at Lysebu (Oslo) on the Cold War in the 1980s with historians from several countries, some with a background from the intelligence services such as Lieutenant General William Odom from the NSA and Douglas MacEachin from the CIA. I talked a lot with Odom, who had been military secretary to President Jimmy Carter’s national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski (1977-81), Chief Army Intelligence (1981-85), Director of the National Security Agency (NSA, 1985-88) and then Director National Security Studies, Hudson Institute. I met him also at later conferences and in Washington at the Hudson Institute. I told him what Caspar Weinberger had said in 2000 about their submarines operating regularly in Swedish waters to test Swedish coastal defenses, but Bill Odom only said shortly: “I am not going to speak about classified information”. It was obvious that what Weinberger had said about the Western submarines, which had operated along the Swedish coast, was still something very, very secret. It was very sensitive. Weinberger’s Assistant Under-Secretary Dov Zakheim told Dagens Nyheter the day after the interview: “if Weinberger wanted to say this, it is up to him”. But he told a friend of mine that neither Weinberger, nor his successor Frank Carlucci, or anyone else will say anything more. Everyone would be silent.

At the Oslo Symposium 2002, Ben Fischer said to me: “Ask Doug MacEachin?” He was responsible for Soviet analysis in the CIA and later for all CIA intelligence analysis. “He may know something”. From 1981, MacEachin was Deputy and later Chief of the CIA's Operation Center, which prepared all the intelligence for President Reagan and for his daily brief. In 1984-89, he was head of the CIA's Office of Soviet Analysis (SOVA) under Robert Gates. Gates was later heading the CIA (Director of Central Intelligence), and he was also Secretary of Defense, but from 1982 he was CIA Deputy Director for Intelligence (DDI). MacEachin held the same position as DDI 1993-95 under CIA Director James Woolsey and the Acting Director Admiral William Studeman. MacEachin was informed of the incident at Muskö in 1982. It was obviously not a Soviet operation. When I asked him about it, he said, “This was like an Underwater U-2 incident,” as if a vessel under CIA or Navy command had been sunk and that an American pilot had survived just as in the 1960 U-2 incident and just as the diver and doctor/officer above had told me. I said: “But the Swedes [unlike the Russians] never went public”. He then turned to Ben Fischer, who was also present, and asked: “Do you know what we're talking about?” Ben Fischer said briefly: “Yes, Ola wrote a paper on it. Ola's lecture was the first lecture I listened to in Oslo.” After this, the conversation was over.

I then asked MacEachin: who I should talk to? except for Studeman, who had been his immediate boss (Studeman had been head of US Naval Intelligence after Butts, then Bill Odom's successor as Director of the NSA 1988-92, then Deputy Director of the CIA under Gates 1991-93 and Woolsey and Acting CIA 1995). MacEachin said: “Haver, Rich Haver”. Richard Haver was Studeman's protégé: the first civilian Deputy Director of Naval Intelligence (under Studeman and Thomas Brooks). In 1989, he was recruited by Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney as his Assistant Secretary for Intelligence. While MacEachin was DDI, Haver was CIA Executive Director for Intelligence Community Affairs. In 2000, he was recruited again by Cheney, but now in charge of intelligence for George W Bush during the transition period until January 20, 2001. He then became Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld’s “Special Assistant for Intelligence”. It was clear that MacEachin had his information from these two. They had apparently informed him about “an Underwater U-2” in Sweden in 1982.

US Secretary of the Navy John Lehman (1981-87) and the author at the Bodø Institute for Defense Studies Conference in 2007 with the Vestfjord behind them, where Lehman's aircraft carriers were supposed to seek radar shadow in a war with the Soviets in the 1980s (Photo: private archive).On 20-21 August 2007, I was in Bodø in North Norway at a conference on US Maritime Strategy, “Politico-Military Assessments on the Northern Flank 1975–1990”. The conference was organized by the Institute for Defense Studies & Parallel History Project with Odom, the former Chief of the British Fleet and Commander-in-Chief Allied Forces Eastern Atlantic, Admiral James Eberle, with General Vigleik Eide, Norway's Chief of Defence (1987-89) and Chairman of the NATO Military Committee (1989-93), and the former US Secretary of the Navy, John Lehman (1981-87). In the Nixon administration, Lehman had worked directly under Henry Kissinger and Alexander Haig. I had written my PhD thesis in the 1980s on “US Maritime Strategy”, which became known as “Lehman’s Maritime Strategy”. In late 1970s, Lehman had been involved in “Sea Plan 2000”, and as President Reagan's Secretary of the Navy, he was the driving force behind the new strategy, a strategy that primarily targeted the Soviet strategic submarines and the bases on the Kola Peninsula. I talked with him a lot, and he was happy with the fact that I had emphasized his arguments and described them correctly in my doctoral dissertation, Cold Water Politics (1989), which had been on the curriculum at the US Naval War College. He referred to me in kind words to a journalist writing for the British Sunday Times in 2008.

Lehman said that the decision on the submarine operations in Swedish waters, which Weinberger had spoken about for SVT, had been taken by a “Deception Committee” under CIA Director William Casey, who already before the transition in January 1981 succeeded in getting Reagan initiate this committee. The committee's task was "deception", to deceive the Soviets. But the task was clearly also to trick the Allies and friends into believing in “Russian offensive actions” to get the Allies to mobilize against the Russians (see Part III).

It was Casey, the National Security Adviser Dick Allen and the Deputy Secretaries of State and Defense, who had made the decision to give President Reagan, Secretary of State Alexander Haig and Defense Secretary Weinberger “plausible deniability”, so they could say: we knew nothing about these illegal activities. Lehman would not say which Swedes were involved. But he added that if he had told me that, he would have to "kill me afterwards”. This was the most sensitive they had. Later, Lehman was talking with Swedish former Chief of Navy Vice Admiral Bengt Schuback, who had invited me to his office 20 years earlier. I asked Lehman again, and he responded: “I already told you that if I tell you that, I will have to kill you afterwards”. Admiral Schuback added: “Many people in Sweden would be happy about that”. The day after, when we went by bus to the military Headquarters at Reitan, I happened to sit close to Admiral Schuback. He looked through his manuscript for his afternoon speech. It was a lot about submarines in Swedish waters. However, when he gave his talk, he had cut out everything about the submarines. John Lehman might have convinced him that bringing up the submarines may get him into trouble. John Lehman had already confirmed to me that they used small Italian mini-subs in Swedish waters to give the US Navy "plausible deniability". In case anything would go wrong, US representatives would able to say: “it wasn't us, and we all know what the Italians are like”.

Sherry Sontag's and Christopher Drew’s book Blind Man's Bluff (1998) deals with American espionage and the deployment of listening devices in Soviet waters. Much of this activity was organized by a liaison office between the U.S. Navy and the CIA, the National Underwater Reconnaissance Office (NURO), which was a cousin of the CIA and the U.S. Air Force equivalent, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), in charge of satellite surveillance. NURO was created in 1969, but it was extremely secret. Formally, it is still secret. Its existence was revealed by Sontag and Drew only in 1998. They wrote that in the early 1970s, President Nixon's Secretary of the Navy John Warner was head of the NURO, while the CIA’s Deputy Director for Science and Technology was his deputy chief. In a conversation with Bill Odom and Doug MacEachin, they said that Rich Haver had been Sontag's and Drew’s central source. But MacEachin said that the submarine operations in Soviet waters were only a part of NURO’s activity. NURO had also operated submarines in Scandinavian waters. At a dinner, I spoke with “a special assistant” to President Clinton. He said there was a liaison office between CIA and DIA ( with officers from Navy Intelligence) that was conducting the operation in Swedish waters. “It was the most secret thing we had," he said. During the late 1980s, NURO is said to have consisted of people such as Bill Studeman, Rich Haver, later chiefs of Naval Intelligence such as Thomas Brooks (1988-91), Edward Sheafer (1991-94), Mike Cramer (1994-97) and Mike McConnell. Both Shaefer and McConnell had been intelligence chiefs (J-2) of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral William Crowe resp. General Colin Powell. I asked John Lehman if he, like Warner, had been heading NURO, which he confirmed. In 2021, when I spoke with Lehman’s friend, Admiral Bobby Inman, who had been both Director Naval Intelligence, Chief of National Security Agency, and Deputy DIA and CIA (see below), he said that the Chief of NURO was always the Director of Naval Intelligence. The Secretary of the Navy controlled the funding, but he was never the formal chief. This applied to both the 1970s and the 1980s, he said. Sontag and Drew had misunderstood Warner's position, and Lehman may have looked more at his informal role. But that would mean that after 1985, Bill Studeman and later Thomas Brooks were chiefs of NURO, while Evens Hineman, and later James Hirsch were their deputies, as CIA deputy directors for Science and Technology. Inman also said that NURO “had zero activity in the Baltic”. In Northern Europe, “the focus was on the Soviet Northern Fleet”, Inman said. If Inman is telling the truth, there would be an even more secret CIA-Navy network “that ran the Swedish-Baltic operations”. We'll see later which these people were.

Admiral Bill Studeman as Deputy CIA (DDCI) and later Acting Director of Central Intelligence with James Hirsch as Deputy CIA for Science and Technology at the home of the Norwegian Chief of Intelligence Major General Alf Roar Berg and with Berg's wife Joe between them. As Director Naval Intelligence, Studeman had been chief of the National Underwater Reconnaissance Office (NURO), while Hirsch was the deputy chief. To the right sits Terje Kristensen, who was responsible for Norwegian underwater analysis, similar to NURO, and then deputy Chief of the Norwegian intelligence service under Berg. Kristensen is cut into the picture but sits in the right place at the table (Photo: private archive).I never asked John Lehman about the 1982 incident. But when Dirk Pohlmann from the German-French TV channel ARTE was going to interview Lehman in 2009, I asked Pohlmann to bring up the Swedish incident in 1982: “the Underwater U-2”. Pohlmann said to Lehman: “The submarine in Sweden that was damaged, it came to be called ‘an Underwater U-2’. What did you mean by that?” Lehman replied: Not just Americans, but also other NATO countries operated submarines in other people’s territorial waters. “In fact, there have been some allegations that there were numerous occasions when they actually entered harbors, naval harbors, and engaged in intelligence collection,” and “the Swedish incident would have fallen into that category,” Lehman said. The term “an Underwater U-2” in Sweden 1982 was well known to him. Key players within the CIA and US Navy with Studeman, Haver, MacEachin and Lehman all reportedly talked about the same incident. They compared the Swedish sinking of a mini-sub to the Soviet downing of the U-2 aircraft. Actually, the 1982 incident was a much bigger scandal for the United States, because it had been directed against a friendly state. It was impossible to talk about it in public. Lehman would only say that this “Underwater U-2” (which must have been under US Navy/CIA command), was at least formally not American, but from another NATO country. It would have been a midget submarine from another Western country operating under US/CIA command.