“An Underwater U-2”: Part III

A damaged midget submarine in Sweden in 1982

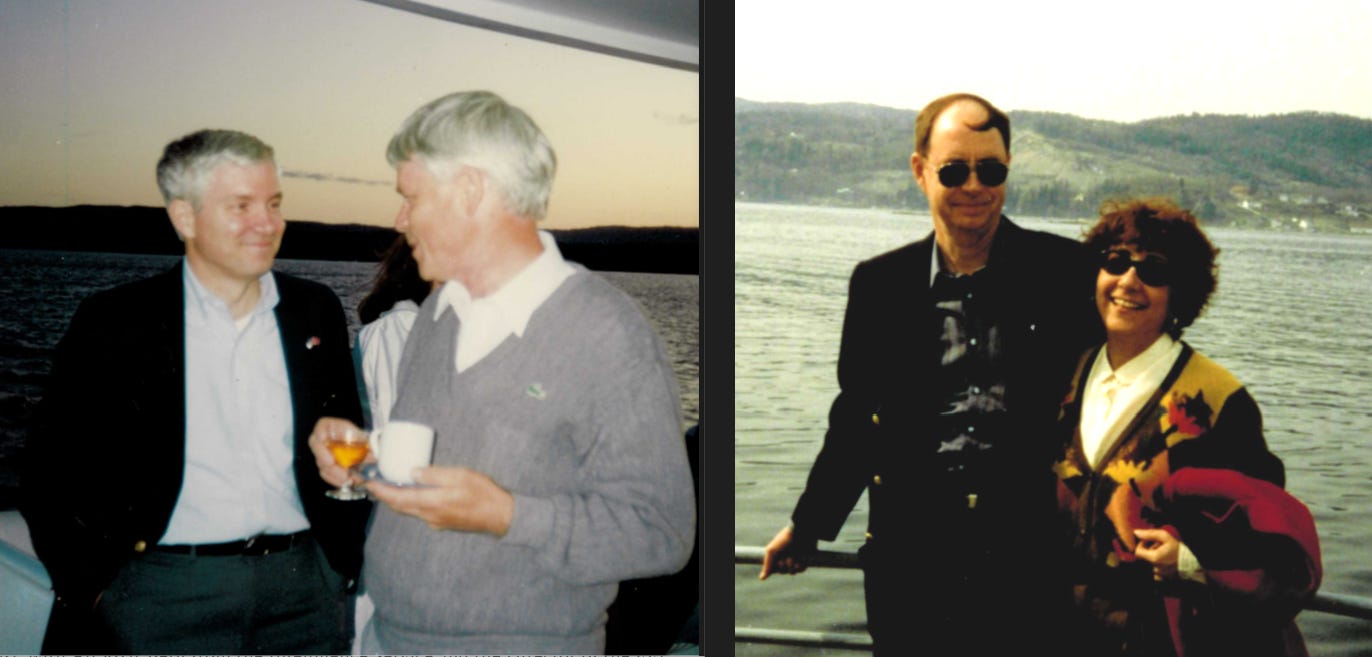

Robert Bathurst with his wife Brit in Sponvika (Norway) on the border to Sweden 1996 (Photo: private archive).7. Robert Bathurst and Bobby Inman

Robert Bathurst had been an interpreter between Nikita Khrushchev and President Eisenhower at Camp David in 1959, he had led the Russian language group in the US Navy, and in 1963, after the Cuban Missile Crisis, he became responsible for the hotline between the White House and Moscow (actually between the Pentagon and Moscow with a link to the White House). He was the night officer in Pentagon in August 1964 when there was a “non-attack” on the destroyer Maddox, which started the US bombing of Vietnam. He called the Chief of Naval Operations in the middle of the night, but he was unaware of the fact that this was false information. However, it was probably the reason why he was picked to become Assistant Attaché in Moscow (1964-67), while the four years younger Bobby Ray Inman was Assistant Attaché in Stockholm. Robert then became Defense Department’s head of Attaché Affairs Eastern Europe (1967-69), and then chief of Naval Intelligence Europe (formally Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence, US Naval Forces Europe, 1969-72), while Inman was at the Naval War College and after that was given the equivalent position for the Pacific as Robert had held for Europe. Robert then held the Admiral Layton Chair of Intelligence at the Naval War College (1972-75) under its president, Admiral Stansfield Turner, who was Bill Casey's predecessor as chief of the CIA or formally speaking Director of Central Intelligence (1977-81). Robert and I talked with Turner while he was in Oslo at the Nobel Institute (1995-96). I had also met him at a PRIO-Pugwash conference in 1988, but at the time I was then far too young to understand what was going on. Nor was Turner a real “insider” like his predecessor, George H.W. Bush (1976-77), and his successor Bill Casey (1981-87). Robert later earned his Ph.D. in comparative literature, he was at the Harvard Russian Research Center and received a professorship at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, where he met Brit, which was why he moved to Oslo in 1990, when her father was getting old. Robert wanted an office where he could sit and write his book, Intelligence and the Mirror: On Creating an Enemy (London: Sage 1993). I recruited him to PRIO in 1991.

Admiral Bobby Ray Inman receives the Distinguished Service Medal from Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger in 1981. He also received his fourth star (Photo: NARA & DVIDS Public Domain Archive).Robert believed that the explanation for the many mini-submarines, that showed off in Swedish archipelagos and naval bases, went back to Bobby Inman (who was the real “insider”) and to his “deal” with the Swedes about the American hydrophones. For Robert, the question was: “How would we get Inman to talk?” The small submarines that appeared in the 1980s were probably the same submarines that were still used to maintain the hydrophones in Swedish waters. Both Robert and Bobby Inman had been the superior commanders of the ten-year-younger later Director Naval Intelligence, Director of the the NSA and Deputy CIA Director Bill Studeman, who also must have known about these submarines in Swedish waters.

In 1998, SVT’s Jonas Olsson wrote to Studeman asking for an interview. He suggested traveling to the U.S. with SVT's “expert Dr. Ola Tunander, who wrote his dissertation on U.S. Maritime Strategy and is a colleague of Robert Bathurst, [Captain] U.S. Naval Intelligence (ret.)”, to quote SVT’s letter, but Studeman rejected SVT's proposal for an interview. In February 2000, a month before SVT aired Jonas Olsson's interview with Weinberger, Robert had sent an email to Norman Channell, his successor as head of Naval Intelligence Europe until the fall of 1981. Robert also sent my early draft of Western submarine activity in Swedish waters, writing: “Do you ever think we can get Bobby Inman to talk?” Channell wrote some nice words about my analysis, but he also added that he probably wouldn’t have been informed, anyway. Despite being chief Naval Intelligence Europe, he was not informed of what “the Agency crowd [the CIA] and the SOF people [the US Navy SEAL or Special Operations Forces]” were up to in his own area of responsibility. He was kept in the dark, and he had no doubt that CIA Director Bill Casey and his crowd could have initiated such operations. Channell also wrote, “I really enjoyed working with BRI [Bobby Ray Inman], but he’s the real sphinx.”

Left: President Ronald Reagan announcing nomination of Frank Carlucci as Secretary of Defense upon the resignation of Caspar Weinberger (Photo: White House / public domain). Right, the official photograph of the Secretary of the Navy John Lehman (Photo: Wikipedia / public domain).By July 1982, Bobby Inman resigned as Deputy Director and for some time as Acting Director of Central Intelligence (and as Acting Director of the CIA) in protest against Casey. Inman had been Director Naval Intelligence (1974-76), Deputy DIA (1976-77), Director of the NSA (1977-81) and in January 1981 he took over as Deputy Director of the CIA from Frank Carlucci, while Carlucci became Deputy Secretary of Defense, National Security Adviser and in 1987 Secretary of Defense after Weinberger (Carlucci didn't tell me much, when I happened to meet him in Washington in 2004). While Casey was concerned with covert action, Inman, with a background in Naval Intelligence and the NSA, focused on technical intelligence collection (but he was also, as “the real sphinx”, deep into covert action as he later became Chairman of the Board of Xe Services, earlier Blackwater). The New York Times believed that it was Casey, not Inman, who should have resigned in 1982. And most influential people, like Senator Barry Goldwater, had pushed for Inman as Director of the CIA already in 1981. Inman was the first officer in Naval Intelligence to get four stars. When he retired in 1982, almost all central figures were there. Carlucci was there, and Chairman of Joint Chiefs of Staff John Vessey and even Casey, and the ceremony was presided over by the Secretary of the Navy, John Lehman, who paid tribute to Bobby Inman by giving a “much too long” speech. “I was a paragon of everything along the way. It was embarrassing”, Inman said afterwards.

Since the 1960s, Inman was close to several Swedish naval officers. He went on holiday with Chief of Navy Vice Admiral Per Rudberg and his family (see Part II). We have reason to believe that Inman was concerned about Casey’s submarine game in Sweden, and that it would possibly reveal Inman's own Swedish hydrophone system and the Italian mini-subs that maintained them. A submarine hunt on a suspected “Soviet submarine” could be revealed as a hunt for some of his own vessels, and then the entire system could be lost.

There was a real conflict between Casey and Inman, and Casey actually vetoed the appointment of Bobby Inman’s Deputy Director of Naval Intelligence, later Vice Admiral Donald Jones, when he was proposed as Director of the NSA. “Casey didn’t want an Inman protégé at the NSA”, one declassified CIA document states. Jones had been Senior Military Assistant to Frank Carlucci as Deputy Secretary of Defense (after Inman had succeeded Carlucci as Deputy CIA), in 1985 Jones became Deputy Chief of Naval Operations replacing Admiral Ace Lyons, and in 1986 he became the Senior Military Assistant to Secretary Weinberger. In 1987, Jones together with then Director of the NSA, Bill Odom, was a candidate to replace Robert Gates as Deputy Director of the Central Intelligence, but both candidates were dropped. Jones had been too close to Admiral Inman, according to a CIA document. Anyway, the conflict between Casey and Inman was so sharp that Admiral Jan Ingebrigtsen, Casey's “opposite number” in Norway, actually believed that my source for “an Underwater U-2” in Swedish waters in 1982 was Bobby Inman, not Doug MacEachin and John Lehman. That is what Ingebrigtsen told me. But this was a misunderstanding. Inman was disciplined. He would not leak classified information. When Doug MacEachin and Bobby Inman spoke on “Intelligence Used to End the Cold War” at the Reagan Library 2011, it was Inman who said that when it comes to the more sensitive things, “you hopefully won’t read about [them] for another 40 years”.

A later successor to Ingebrigtsen as Chief of the Norwegian Intelligence Service, Major General Alf Roar Berg (1988-93), described Bill Casey as “completely crazy”. Berg had been “the opposite number” of CIA Director Robert Gates (1991-93), and Gates had been Deputy CIA under Casey. Berg had after that been “the opposite number” to Bill Studeman, who took over as Deputy and later as Acting Director of the CIA. General Berg told me about an emergency meeting, they had in Washington in connection with the Kongsberg Toshiba scandal. This was a meeting between the United States on the one hand (with the then Chief of Naval Intelligence, Bill Studeman and Admiral Crowe’s man, Weinberger's Assistant Secretary of Defense Richard Perle), and Norway on the other (with Minister of Defence Johan Jørgen Holst, with Alf Roar Berg from the Intelligence Service and the Director of the FFI, the Defense Research Institute, Erik Klippenberg). Perle wanted to punish Norway for the “leakage” of high technology to the Soviet Union, similar to how he had punished Sweden in the early 1980s (Schweizer, 1994), but this was stopped by Admiral Studeman, who said that Norway was responsible for much of the raw intelligence that the United States has, including 90 % of the Soviet submarine signatures that the US Navy has in its archives. It would be a mistake to punish Norway. Richard Perle had to back down.

CIA chief Robert Gates and US ambassador to Norway Loret Miller Ruppe visits the Norwegian Chief of Intelligence Major General Alf Roar Berg, here on the Oslo fjord in June 1992 (Photo: private archive).Left: CIA Director Robert Gates and Chief of Intelligence Alf Roar Berg on Oslo Fjord 1992. Right: Deputy CIA Director Bill Studeman with Alfs wife Joe on the Oslo fjord in 1993. During his five years as chief of Norway’s Intelligence Service, General Berg had several key figures as his US opposite number: General Odom, Admiral Studeman, Robert Gates and James Woolsey. Both Gates and Studeman were Inman's protégés, and Studeman had an almost identical career path as Inman: Director Naval Intelligence, Director NSA, Deputy and Acting Director of the CIA and four stars.The Western submarine operations, not least the American operations were so secret that nothing could be written down on paper. According to Defense Minister Weinberger, it was “Navy-to-Navy consultations” that led to joint decisions. The Swedish–American agreements were maintained through personal ties between most senior officers, he said. At a lunch I had in June 1989 with Admiral Crowe's predecessor as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General John Vessey (1981-85), he said: “When it comes to Sweden, there was only one rule: Nothing on paper”. It was the personal ties between some American and Swedish officers that guaranteed the agreements that were most secret, and which ensured that the Swedish military planned for an American presence. During a lunch in connection with a Nuclear Weapons Conference in Norway in June 1993, I asked former CIA Director and Defense Secretary James Schlesinger about his view on Sweden during his time in the administration. He asked back, “Which Sweden? The ‘political Sweden’ or the military? The ‘military Sweden' planned for us to come as soon as possible.”

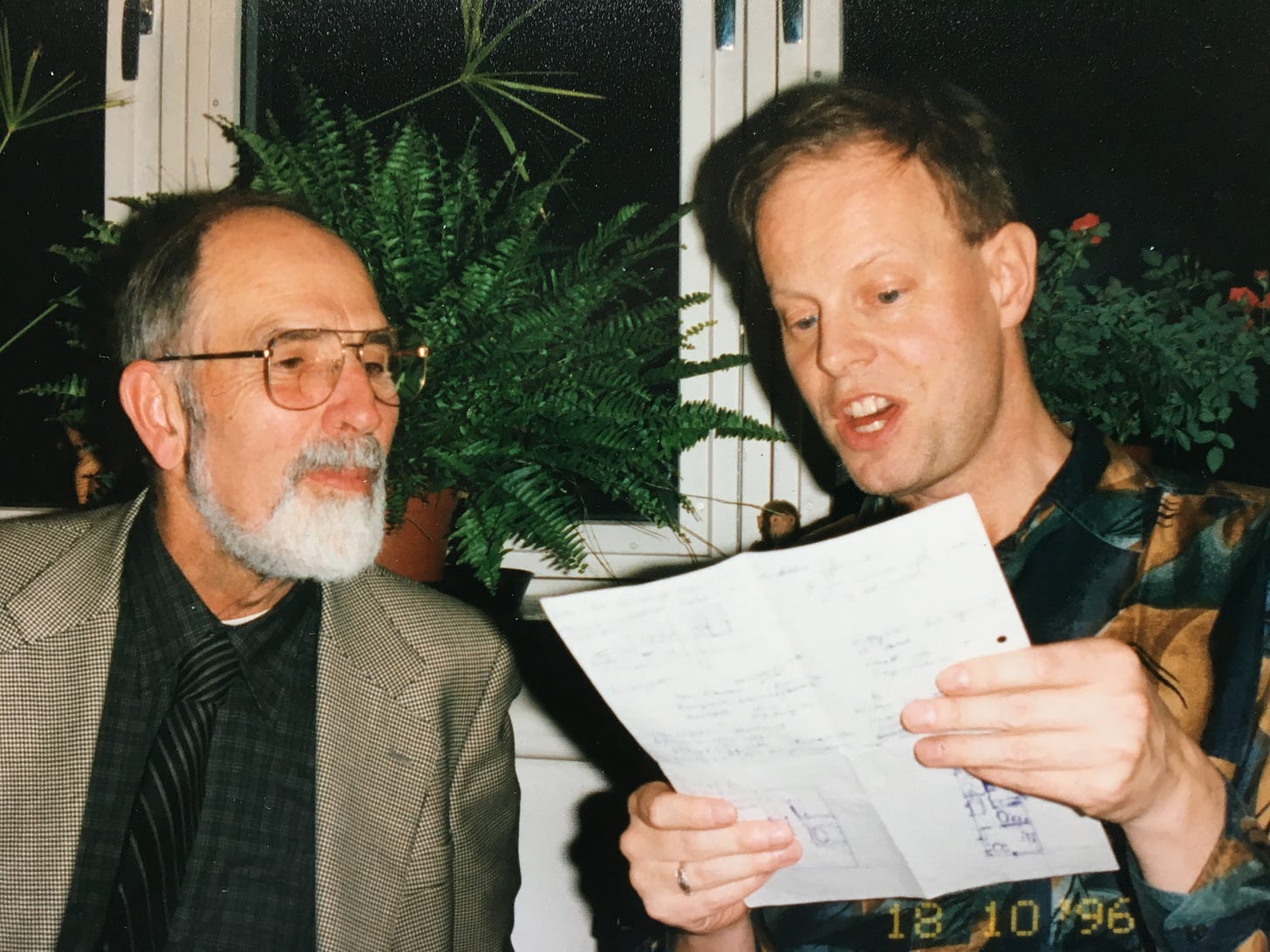

Robert Bathurst and the author on my mother's 75th birthday in 1996 (Photo: private archive).There was a small Swedish military elite with some high-ranking officers, who worked for a Swedish-American consensus together with a similar elite in the United States. Caspar Weinberger told SVT in March 2000 that there were never any formal agreements with Sweden. “It was conversations that led to a consensus”, he said. But if someone violated this “consensus”, these verbal agreements, there were no legal sanctions, only physical force. In April 2000, a month after Weinberger had explained to SVT that they had regularly operated Western submarines in Swedish waters, Robert Bathurst flew to California, to his friends at the Naval Postgraduate School with my transcript of SVT's full interview with Weinberger. Robert spoke about the intrusions in Sweden with several former colleagues such as Norman Channell and the Strategy Professor Wayne Hughes, who had been a military adviser to the Under Secretary of the Navy, the later CIA Director James Woolsey, and they spoke with Defense Secretary Weinberger’s Military Assistant, Robert said. In other words, they spoke with Robert’s one year younger colleague from Naval Intelligence, Inman protégé, Vice Admiral Donald Jones, and they came back to Robert and said: “Don't touch it. It is physically dangerous”.

After Robert came back from the US, he explained what had happened. He had an e-mail-communication with an officer from Naval Intelligence on 6. May and with one officer from U.S. Navy SEALs, a “frog”, on 24-25. May. He wrote: “I am trying to help a colleague, a Swedish Researcher […] If it is too sensitive, I drop it”. Robert died a couple of weeks later in June, 73 years old. He did not wake up in the morning when his wife Brit was going to serve him tea.

Media on submarine hunt in Hårsfjärden at Muskö 1982 (Screenshot Swedish TV News).8. An explanation of the operations

The origin of the US Navy’s and the CIA’s operation with small submarines in Swedish ports, archipelagoes and naval bases in the 1980s seems to have originated in Bobby Inman's “deal” about the deployment of hydrophones from the late 1960s, with someone on the Swedish side, most likely with Defense Minister Sven Andersson and Chief of Navy Vice Admiral Åke Lindemalm, From around 1970, these hydrophones were maintained by small Italian-built submarines, which were brought to the Baltic Sea and to the Swedish archipelagoes on converted civilian merchant ships, such as tankers with a compartment for these submarines. When senior officials in the Reagan Administration, and especially CIA Director William Casey, saw Sweden, and all of Scandinavia, as a problem, as a countries bordering the Soviet Union but lacking a “realistic understanding of the Soviet threat” or rather of “having developed a too independent position” vis-à-vis the USA and the UK, it became natural to let these submarines demonstrate their presence in Swedish waters by showing their periscope, their sails and sometimes the entire submarine, in order to make the Swedes and other Scandinavians take the Soviet threat seriously and to lean more towards the Western powers.

This was also done in Norwegian waters, but “we did not go public”, a Norwegian former deputy chief of intelligence told me. While the Swedes made a big fuss about intruding submarines, “we tried to keep a low profile”, he said. We proposed to the Swedes that they should do the same, “but they didn’t want to listen to us”, he said. Former Commander-in-Chief Southern Norway, Vice Admiral Carsten Lütken wrote a letter to me: “We made a point of saying that it wasn’t anything, if we didn’t find anything. […] We did not always know what our allies did,” then it was better to keep quiet, Lütken said. This was a very different approach from that of the Swedish admirals, who wanted to make the headlines, and this was also what the the British and the US had proposed to them.

According to a number of British Foreign Office documents from 1979-82, one must “talk seriously” with the Norwegians. Norwegian Prime Minister Odvar Nordli (1976-81) had in his New Years Speech 1981 spoke about the possibilities of the Nordic Nuclear Weapons-Free Zone. This was unacceptable to the British and the Americans and they had to change the Scandinavian policy. Nordli was replaced immediately, but that was not enough. The Norwegians were out on “a slippery slope”, the British Defence Ministry wrote in one document, and the Swedes were an even bigger problem. One had to do something drastically, and it was obvious that the problem was not just the political leadership, but the population as a whole. One had to change the mentality, the political views.

On 27 October 1981, a senior navigation officer on a Soviet Whiskey class submarine ran his submarine up on a rock close to the Swedish Karlskrona Naval Base (“The Whiskey on the Rocks”-incident). When the submarine stranded on a small island, he had been running the propellers forward in an attempt to get the submarine higher up on the island (which was revealed by the divers investigation). The Chief of Staff of the Naval Base, Commander, later Commodore Karl Andersson was given orders not to question him. The other central officers on the submarine were all questioned by the Swedes, by Andersson, but not the senior navigation officer, Josef Avrukevich, who had been responsible for this very strange navigation. Some senior officers in Sweden knew about this incident in beforehand, according to a British intelligence document, Swedish Chief of Defence General Lennart Ljung wrote in his diary. The US Naval attachés had arrived in Karlskrona just before it happened. Andersson told in a recorded interview that it happened two very strange things this morning: firstly, two US naval attachés turned up at his office early in the morning without he, as a chief of staff, had been pre-notified, which had never happened neither before nor after this incident; and secondly, a Soviet submarine had stranded on an island deep into a fjord that was so narrow and shallow that you couldn’t dive and you would have difficulty to turn around. Why would the Soviets go with a submarine on the surface deep into a neutral country and into a fjord, where it was no way out? It made no sense, but it changed Swedish and Scandinavian mentality.

After this 1981 incident, the Danish political-military representatives told their British counterparts that “it would take a long time for the Soviet Union to regain its credibility, and that the incident had been the kiss of death for the proposal for a Nordic Nuclear Weapon Free Zone”. But even more important, after the dramatic submarine hunt at Muskö Naval Base in October 1982, the British ambassador to Stockholm wrote that Sweden's foreign minister now began to speak in more “realistic” terms. They believed it were Soviet submarines. While the former state secretary for defense, Karl Frithiofson, who had a summer house almost next door to Andersson and Lindemalm, told his son after a military leadership meeting on 1 December following year that the submarines were from the west.

That the intention of the US and British use of submarines deep into Swedish waters were to increase Swedish “readiness” and awareness of the Soviet threat, became clear in year 2000 after the interviews with the then US Secretary of Defense Weinberger, with the British Minister of the Navy Keith Speed and later also with the interview with former US Secretary of the Navy John Lehman. Both Weinberger and Speed said that they operated submarines in Swedish waters to test Swedish readiness, to see “how far we could get” without you detecting us, to quote Speed. But it was obvious to everyone that it was also about something else. The operations changed Swedish perception of the Soviet Union. I wrote in the preface that 25-30 % of Swedes up to 1980 had perceived the Soviet Union as a direct threat or as hostile to Sweden. Three years later, in 1983, after claims of almost daily observations of submarines in Swedish waters, this figure had risen to 83%. Sweden had turned into a different country. The whole public opinion changed. Sweden was tricked or deceived. According to John Lehman, it was a “Deception Committee” under CIA Director William Casey that had taken the decisions about the Swedish operations, which Weinberger had talked about, and according to key a figure in the CIA, it was Lehman's protégé, Admiral Donald Jones’ predecessor as Deputy Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Ace Lyons who had been responsible. Let's look at this:

CIA's former chief analyst for Russia Fritz Ermarth speaking before the 1999 Congress (C-Span, Screenshot). Right: Admiral Ace Lyons with former Secretary of the Navy John Lehman, when Lehman is given “The Freedom Flame Award” in 2011.Fritz Ermarth had been “Special Assistant” to the CIA Director in the 1970s. From 1983-86 he was the CIA’s National Intelligence Officer for the Soviet Union in charge of the National Intelligence Estimate also for the Soviet Navy (in collaboration with Navy Intelligence, with Studeman and Haver, and with Navy Secretary Lehman). In 1986-88, Ermarth was Special Assistant to President Reagan and head of Soviet and Eastern Europe on the National Security Council, while in 1988-93 he chaired the CIA's National Intelligence Council directly under CIA directors Webster, Gates, and Woolsey. He worked with Gates for 20 years and, along with Doug MacEachin, he was perhaps the most important CIA analyst in assessing the Soviet Union in the Reagan Administration. Ermarth said that Admiral James “Ace” Lyons had been responsible for some “very secret operations in northern Europe”, in other words in Scandinavian waters. I informed the TV channel ARTE with Dirk Pohlmann, who flew over to the United States in 2014 and interviewed Admiral Lyons. Parts of the interview was sent in the ARTE/ZDF program “Täuschung: Die Methode Reagan”, on 5 May 2015. Lyons said that CIA Director Bill Casey had called him [in October-November 1983 after the bombing of US Marines in Beirut on 23 October and just after Casey was back from Stockholm] and asked him to prepare for some Special Forces to carry out physical attacks against their own naval bases and to test the US readiness at all their bases worldwide, similar to what he already had done in northern waters, in other words in the northern Europe. Lyons said that instructions are not sufficient to make local commanders raise their awareness and their readiness. You had to be “physical”. “And I had the approval of the Secretary of the Navy John Lehman to go ahead and do this”, he said. ARTE asked about the operations in Swedish waters in the 1980s: did you try to increase Swedish readiness as you later tried to increase the readiness of American bases with physical actions? Pohlmann asked: “Were the submarine things in Sweden, was that a similar idea: to get in there and raise the attention of the Swedes?” Lyons replied, “Yes, right, right, right. [...] It was my staff, me! Right here! I'm the one who put that together: the deception formations, all the decoys, and all that was me and my staff that did that.” Pohlmann and ARTE continued: “So, were the submarine incursions in Sweden [made] to make the Swedish military understand: ‘we can do this, go ahead with us?’” Lyons replied: “Well, I'm sure they recognized what we were doing.” Pohlmann continued: “Was the stranding of the submarine in Sweden [The Whiskey on the Rocks], was that also a deception operation?” Lyons replied: “Yeah, could have been. [Long big laughter]. Yeah, yeah, yeah.” Pohlmann asked: “When you look at these things that have a signature of these. I can see a similarity”. Lyons continue: “Could be, yeah”. Pohlmann continued: “But you are not allowed to talk about it?” Lyons replied: “Some things you still keep to yourself”. When Lyons left the interview, he was irritated. He shouldn’t have told all of it. He had become too enthusiastic. When I asked a US Navy officer a couple of years later about Admiral Lyons comments, he simply said, “Lyons had said too much”. He died in 2018.

It was clear that these operations in Swedish waters were not just about testing the Swedish Navy’s readiness, “like testing a weapon”, as Caspar Weinberger had said, but that it was – and perhaps primarily – about deception. The communication went directly from CIA Director Bill Casey to Admiral Ace Lyons. It was about totally changing Swedish and largely also European public opinion. According to a 1981 document, US “Perception Management” operations were to be launched “to raise the [European] perception of Soviet activity in the region and trigger some [European] response”. The idea was in this case to make the Swedes and the Europeans take the Soviet threat more seriously. Those US actions were not directed primarily against the Soviet Union or its allies. The implication is that the US should target US friends (or allies) like Sweden so that they would become aware of “the real Soviet threat”, for example, by initiating underwater provocations believed to be Soviet military action (“deception”).

The target, as described by Deputy Undersecretary for Defense for Policy General Richard Stilwell (1981-85), was apparently some Western states that didn’t adhere to the US discourse and didn’t take the Soviet threat seriously enough. General Stilwell recommended US use of provocations to raise “the perception of Soviet activity” to “trigger some response” in the friendly countries (read Sweden). But to target friends was extremely sensitive. The US intelligence historian Jeffrey Richelson writes: a cancellation notice for some very sensitive documents was sent out at the request of Stilwell on 4 February 1983. “The memo asked recipients to ‘remove and destroy immediately’ any copies of two Defense Department directives in their possession” titled “The Defense Special Plans Office”. Something serious had happened, probably in autumn 1982, which demanded some action. In March 1984, a Presidential Directive (National Security Decision Directive Number 130) concluded that PSYOP (psychological operations) and “Perception Management” were central, but these operations presupposed, “imminence of war”. This Presidential Directive had probably been required to clean up so that the system would not operate on its own. Something serious had happened in the autumn of 1982, and an order had been issued on February 4, 1983, for some very sensitive documents to be shredded.

This is probable the explanation for the US and British claims at a meeting of NATO's most central intelligence committee, the Intelligence Steering Committee, in the autumn of 1988. The Norwegian Chief of Intelligence Alf Roar Berg explained that the US and British chiefs of military intelligence (presumably Lieutenant General Leonard Perroots and Lieutenant General Derek Boorman) had claimed that a Soviet military attack on the West was “imminent”. All other states in NATO supported Washington and London, but Norwegian Military Intelligence knew that Russian preparedness was low and that these claims about an “imminent war” were false. These claims were made for other reasons. General Berg stood up to the British and the Americans. One after another switched to the Norwegian side. The US and the British had to back down. The question is why Americans and British sought NATO to accept such obviously false claims. There are two reasonable explanations. Firstly, they wanted to justify continued PSYOP and “perception management” operations with, for example, submarine operations in Swedish waters, which would demand “imminence of war”. These operations continued until the early 1990s. Secondly, by claiming that a Soviet invasion was “imminent”, the British and the American could get the European countries to seek Anglo-American protection, just as the United States and Britain throughout the 1980s had done by letting their own submarines act as Soviet submarines in Swedish waters to get Swedes and others from the Nordic countries to turn to the United States and Britain for protection, to ensure an American hegemonic discourse. The sinking of a small submarine in Hårsfjärden in 1982 was an accident that was never allowed to become public.

“The Underwater U-2” in 1982 was probably a much more serious incident than the U-2 incident of 1960. One might say that it never was made public, because there was a Swedish-American elite, a “deep state”, that has been able to hide any sensitive event. And because there were no formal agreements, it was all about physical force. The “Underwater U-2 incident” on October 5, 1982, didn’t happen, because it was not allowed to happen.

I have recently written about all this in a Swedish book, Det svenska ubåtskriget [The Swedish Submarine War] (Stockholm: Medströms 2019). It was reviewed by some of the most experienced ambassadors in Sweden, the Swedish longtime Moscow ambassador, Sven Hirdman, who in October 1982 was State Secretary for Defense and, according to the Swedish Chief of Defense, he was acting Defense Minister; by Pierre Schori, who in the 1980s was State Secretary for Foreign Affairs and responsible in Foreign Ministry for these questions (later he was ambassador to the UN and a minister); by Mathias Mossberg, responsible for the Soviet affairs in the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, head of the Ministry's analysis group and Secretary General of the official Swedish Submarine Inquiry about the intrusions in the1980s (2001) and Secretary General of the official Swedish Security Policy Inquiry about the Swedish Cold War History 1969-1989 (2002); and finally by the editor and journalist Sune Olofson, who for 25 years was defense reporter and op-ed editor at the Conservative daily Svenska Dagbladet. These four, all of whom have played a central role for the official Swedish perceptions of the intrusions of the 1980s, and who had been major representatives of the official Sweden, wrote a common very positive review of my book, but none of Sweden’s four major newspapers (Svenska Dagbladet, Dagens Nyheter, Expressen and Aftonbladet) accepted the article. These questions are still far too sensitive for anyone to raise in the Swedish media.

The problem with sources

I wrote my PhD thesis on weapons technology, US naval strategy and geopolitics in Northern Europe. It was a thesis on security policy and military strategy, and my first Swedish draft was published by FOA (The Swedish Armed Forces Research Institution) in 1987. This report, “Norden och USA’s Maritima Strategi”, became one of two main books at the Swedish Military Academy curriculum, while my thesis on Maritime Strategy, Cold Water Politics: The Maritime Strategy and Geopolitics of the Northern Front (London: Sage, 1989) was on the reading list at the U.S. Naval War College. I lectured on it at the U.S. Navy's Center for Naval Analysis at the Pentagon and at the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. From 1986 to 2016 I attended a large number of security policy and defense policy conferences in Europe, the USA and Asia (in China and India). Many Nordic conferences were organized by the International Affairs Institutes and by the Peace Research Institutes, but also by the Institute for Defence Studies. I participated at conferences that were organized by the U.S. Navy, the Royal Navy and the Canadian Navy, and by universities like Harvard University. I was at historians' conferences, at peace research and political science conferences, and at conferences on intelligence and military strategy. Naturally, I was also at the large International Studies Association Conventions held annually in the United States or in Canada with thousands of participants.

Many conferences resulted in books, in which I contributed with chapters. For some of these books, I was the editor or co-editor and some of them were on the reading list at universities in different countries, like University in Oxford. At many of these conferences, there were academics, but also officers and civil servants, sometimes most senior officers and ministers and their advisers from the Nordic countries, from the United States, Great Britain, Russia and other European states and from India and China. There were never American, Russian or Chinese presidents or prime ministers present, but there were several of their closest advisors. I had conversations with U.S. defense secretaries, navy secretaries, chiefs of defense, directors of the CIA and their deputies and directors of the NSA. I had talks with chiefs of defense, chiefs of navy and chiefs of intelligence from several countries. We had lunches, dinners, and long conversations together, which sometimes got into issues that may have been classified. In the United States, this is not uncommon. As a researcher, you meet a secretary of the Navy or a director of the CIA, not as a journalist, who primarily asks questions, but as a partner with whom you discuss topics of common interest. Many of my sources belong to this category. Someone can remember something wrongly. One can make a mistake, but there are many sources that say almost the same thing, and we can hardly ignore the fact that Swedish divers say they have experienced things, that their commanders confirm, and what is consistent with what the most senior representatives of the CIA and US Navy have said. When top officials in the CIA and US Navy say that there was an “Underwater U-2” in Swedish waters at Muskö in 1982 and that CIA Director Casey and Admiral Lyons were responsible, and when Lyons himself says the same, one must take that seriously.

A lot of material can also be found in my books: Det svenska ubåtskriget [The Swedish Submarine War] (Stockholm: Medströms förlag, 2019, 416 pp. and 1.2 kilo). (https://www.medstromsbokforlag.com/portfolio-c17to). It was launched at the Swedish Army Museum and the Swedish ABF in autumn 2019 and at Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) on 25 February 2020.: “The hidden game of power – Submarines in Scandinavian waters” (https://www.nupi.no/arrangementer/2020/det-skjulte-maktspillet-ubaater-i-skandinavisk-farvann). My book Navigationsexperten [The Navigation Expert] (Stockholm: Karneval förlag, 2021) addresses the 1981 event, “Whiskey on the Rocks”. I have previously written several books on the 1982 submarine event such as Hårsfjärden (Stockholm Norstedts förlag, 2001) and The Secret War against Sweden: US and British Submarine Deception in the 1980s (London: Frank Cass; Naval Policy and History Series, 2004), and a 400-pages report for Stockholm and Gothenburg University, Spelet under ytan: Teknisk bevisning i nationalitetsfrågan för ubåtsoperationen mot Sverige 1982 [The Game below the Surface: Technical Evidence for the Nationality of the Submarine Operation against Sweden in 1982] (the Research Program: Sweden during the Cold War, Report 16, revised edition). https://files.prio.org/files/projects/Spelet%20under%20ytan/Spelet-under-ytan.pdf ; ARTE’s documentary (in German), “Täuschung: Die Methode Reagan” was screened on 5 May 2015 and deals with the same theme with interviews with Casey’s close assistant Herb Meyer, with Navy Secretary John Lehman, with Admiral Ace Lyons, with the Swedish Commodore Karl Andersson, with Defense Minister Sven Andersson’s close assistant Ingemar Engman, with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and Foreign Minister Boris Pankin, with Ambassadore Mathias Mossberg and Ola Frithiofson and with myself.

Hei Ola,

Her er Pohlmann-filmen med engelske undertekster.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kETldsGUr-k&t=1262s

Jeg har den med norske også, hvis det er interesse. De kan lastes ned fra Youtube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kETldsGUr-k&t=1262s