The Submarine War against Sweden: Part II

US and UK operations in the 1980s: Twelve remarkable facts

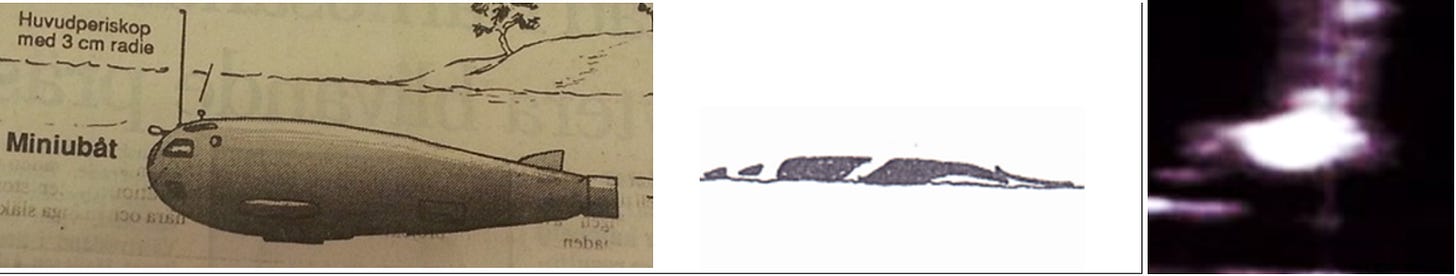

Three Maritalia midgets from the 1980s: an unknown vessel from 1980 and two 3GST9 (10 meters) from 1983.Left: The “Type 1” submarine as presented by Svenska Dagbladet (1987) with very similar shape, length, hatch, and periscope as the Maritalia vessels (the drawing is based on leaks from the intelligence service). A drawing from a photo of a surfaced “Type 1” in the far north of Sweden in 1987. Right: A sonar image of a “Type 1” from Karlskrona Naval Base in 1984.From left: a 20-25 meters’ “Type 2” submarine seen in the vicinity of the Muskö Naval Base on 4 October 1982, a drawing of the same submarine made after the description of the observer. The “Type 2” had a high snorkel mast behind the sail. Right: a 20-25 meters’ Type 2 submarine passing through the narrow channel only a few kilometers from the former position but five years later in July 1987. The submarine had two SDVs (Swimmer Delivery Vehicles) and a high snorkel mast behind the sail, very similar to the Italian-built COSMOS SX-506 (23 meters). In addition, the “Type 2” had a wire from the bow to the top of the sail similar to all COSMOS submarines (see below). It is remarkable that these submarines turn up on the surface, deep inside shallow channels in the inner archipelagos, also in populated areas.Two COSMOS SX-506 (23 meters) sold to Colombia with a high snorkel mast behind the sail and a wire from the bow to the top of the sail similar to the “Type 2” submarine.Left: Sonar image of a “Type 2” submarine from Stockholm Archipelago in May 1984 (the bow shape of the hull is a distortion from the sonar). One can see a light shadow from a small sail at the center of the hull. The length is said to be 28 meters (or rather 25-30 meters). The hull shape of the “Type 2” is rectangular similar to all COSMOS submarines. Right: drawing of a COSMOS MG-110 (28 meters). The snorkel mast could be raised from horizontal to vertical, which has also been seen on the “Type 2”. A fifth remarkable fact is that the Swedish documents declassified in 2001 showed that Swedish Military Intelligence had nothing pointing to the Soviet Union. The Swedish top-secret report from the Naval Analysis Group signed by the Chief of Defense (18 December 1987) described details of different intruding submarines, their length, shape, color, escape hatches and periscopes and other masts, but in the following report to Prime Minister Ingvar Carlsson, former Chief of Military Intelligence Major General Bengt Wallroth (with Ambassador Jan Eliasson and Hans Dahlgren from Prime Minister’s Office) wrote that these “Type 1 and Type 2 submarines” were not consistent with any known Soviet midget submarine. Swedish intelligence had nothing pointing to the Soviets, he said. This was also the conclusion of the 1995 Submarine Commission, where Wallroth was its Secretary General. The 1983 Commission had claimed that the very fact that there were midget submarines was proof of Soviet operations. “Only the Soviets had midget submarines”, the Chairman of the Commission argued. But this was a lie. At the time the only offensive midget submarines were from the West. The Soviets did not have the capability for such advanced midget submarine operations, a Norwegian intelligence officer said. As we will see below, the details of these two types of intruding submarines are identical to the details of two very specific Western submarines.

As a Civilian Expert of the 2001 Submarine Inquiry, I looked at drawings and descriptions made by observers of submarines. None of these descriptions were consistent with a Soviet submarine. A 1984 top-secret document for the Chief of Navy Admiral Per Rudberg made a first description of the “Type 1” and the “Type 2” submarines, of the 10 meters’ drop-shaped “whaleback” and the regular small “Type 2” submarine 20-30 meters with a high snorkel mast behind the sail. In July 1982, a small dropped-shaped vessel had been seen on several occasions in Stockholm northern archipelago, and on 30 September, it was seemingly entering the narrow channel at Muskö Naval Base into Hårsfjärden. On 5 October, a small vessel, described as a “black hill”, was seen on the surface. This “Type 1” submarine was hit by a depth charge. The 1984 document wrote that there had been 15 observations of “Type 1” in 1983. In 1984, there were a series of sonar images of a “Type 1” close to Karlskrona. All the details seemingly fit with the Italian Maritalia midgets from the 1980s. On 4 October 1982, a 20-25 meters’ “Type 2” submarine surfaced in a narrow channel outside Hårsfjärden. It had a regular sail and a high snorkel mast behind the sail (see drawings above). Later observations of the “Type 2” at short range showed that it had a wire from the bow to the top of the sail and that it could raise its snorkel mast from horizontal to vertical. It could also carry two small SDVs. There was a sonar image of this 20-30 meters’ submarine. In the early and mid-1980s, there were no such Soviet submarines, but all details fit with the Italian-built COSMOS submarines used by the US Navy to maintain a system of hydrophones in Swedish waters (see below).

On 4 October 1982, there was an observation of a huge submarine sail (close to “10 meters” and “higher than wide”) in Stockholm southern archipelago. The Soviets did not have such submarines. The shape and length would imply a Western submarine. One might argue that the observers had had too much fantasy, but they were taken seriously, and the descriptions did not fit with Soviet submarines. The following day, a submarine, just below the surface, was measured to 35-40 meters (or 40 meters). There was in 1982 no Soviet submarine with a length of 17-70 meters (except for the 21 meters’ oceanographic laboratory Benthos-300 and the 28 meters’ deep ocean bathyscaphe Project 1906; neither of them could have been used in an offensive operation). But the lack of evidence of Soviet activity was classified as top-secret, and no attempt was made to compare these descriptions with Western vessels. The Chairman of the 1983 Commission, Sven Andersson, argued that a keel print on the sea floor was proof of a Soviet submarine. “Only Whiskey class submarines have a keel”, he said. The keel was said to be identical to Karlskrona submarine in 1981. However, it was later confirmed that no regular Soviet submarine had an external keel, while several Western submarines had. The divers’ film of the 1981 Whiskey class submarine in Karlskrona (declassified after 2010) shows that it had no keel. The 1983 Commission’s statement was a blunt lie. Swedish naval officers spoke about Soviet submarines, but documents declassified in 2001 showed that these naval officers had nothing to support their claims. The fact that descriptions of submarines did not fit with Soviet vessels forced scholars to think in terms of Western submarines.

Left: The Conservative Svenska Dagbladet the day after the Submarine Defense Commission press conference on 26 April 1983. Headlines: “Harsh Swedish protest against the Soviet Union: STOP THE INTRUSIONS”. “Soviet submarine in Stockholm City” and “Sweden deep freezes ties to the Soviet Union”. The photos show Soviet Ambassador Boris Pankin having received the Swedish protest note, Chairman of the Submarine Defense Commission, former Defense and Foreign Minister Sven Andersson and Swedish Ambassador Carl de Geer leaving Moscow. “Reporting about the submarines: page 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12.” Second image: Prime Minister Olof “Palme announces worse relations. We have lost confidence in the Soviet Union” with a photo of Palme and Foreign Minister Bodström. Right: Dagbladet in Norway comments on the Hardangerfjord-events. The Norwegian Chief of Navy Vice Admiral Roy Breivik says: “THE TASK OF THE SUBMARINE: TO BE SEEN”. A sixth remarkable fact is the timing. From a Soviet point of view, the planning of the operations appears to have been extremely counterproductive. We all knew in-beforehand that the press conference of the Submarine Defense Commission was announced for the 26 April 1983 and that hundreds of journalists and the global media would turn up. It was a most significant event for Sweden that year. Why would then the Soviets operate a small vessel deep into Stockholm harbor the same morning? This does not make sense. There was both visual and technical evidence in the Stockholm harbor. If this had been made public by the Defense Staff, this would have added fire to an already dramatic day. To argue that the Soviets were the culprit would imply that they didn’t care about Western perceptions, which contradicts Soviet activities in other fields.

The following day, a submarine was reported on the surface in Southern Norway, in Hardangerfjord. A large anti-submarine operation started. Norwegian Chief of Navy Vice Admiral Roy Breivik described the task of the submarine: “to be seen”. Global media left Stockholm for Norway to follow the Norwegian drama, to continue their reporting on “Soviet subs” entering Scandinavian waters. The next days, “four submarines” turned up at Sundsvall 300 km north of Stockholm and then there was a submarine on the Swedish west coast. The Stockholm press conference was accompanied by the sound of depth charges and anti-submarine rockets, as if these events had been orchestrated. Journalists were flying from one live thriller to the other, shocked by the many “Soviet intrusions”: “The Soviets are coming”, they said. The public opinion perceiving the Soviet Union as a threat or as unfriendly changed drastically in three years from 27 % to 83 %. Sweden became a country focusing on defense. Why would the Soviets do this? Why would they push “neutral Sweden” into the arms of the enemy: United States? Swedish Commodore Nils-Ove Jansson (2014) has argued that the relations between Moscow and Washington were tense, which is true, and that military matters had first priority to Moscow, but whether Sweden would turn to the U.S. to receive support or not was certainly an issue of priority also to Moscow, and if these submarines were preparing for a military attack, why did they turn up on surface demonstrating their periscopes and sails in densely populated areas? These were certainly not Soviet submarines.

Admiral Bobby Ray Inman 1981 (Director Naval Intelligence 1974-76), Rear Admiral Sumner Shapiro (1978-82), his replacement Rear Admiral John Butts (1982-85), and his replacement Rear Admiral William Studeman (1985-88). None of these Directors of Naval Intelligence pointed to any significant Soviet activity in Swedish waters. If there had been any such operations, they would have told the House Armed Services Committee.A seventh equally remarkable fact is that the U.S. did not believe in any significant Soviet activity. Soviet penetrations deep into Swedish archipelagoes were not taken seriously by US Naval Intelligence. Former Director of Naval Intelligence and Deputy Director of Central Intelligence Bobby Ray Inman told me and my colleague Ola Frithiofson that Soviet submarines “went into Swedish territorial waters, they crossed the 12-miles’ territorial limit, but they never entered the archipelagoes”. The intrusions into Swedish naval bases and harbors would accordingly have a different origin. He also told Ola Frithiofson that the U.S. Navy knew where the Soviet submarines operated, because they had deployed hydrophones along the Swedish coasts. I have six sources that have spoken about these hydrophones. They were maintained by “small Western special purpose submarines”. One source told that they were Italian. When Bobby Inman became Deputy Director of Central Intelligence, his Director William Casey wanted to use these small vessels to change the mentality of the Swedes, but it was very secret. They didn’t tell the Swedes. At the time, a Swedish Defense Minister delegation to Washington was briefed by senior US Naval Intelligence officers. Despite that the Swedes were pre-occupied by their submarine intrusions and despite that the U.S. usually would take intrusions into the waters of their friends and allies very seriously, they had not been interested in the Swedish submarine problem. They told the Swedes to rather look to the West, I was told by one participant in the Swedish delegation. Swedish Defense Minister Thage G. Peterson had a similar experience. He was also asked to look to the West (see below). He wrote in 1999:

“[I]t concerns the American total lack of interest for the Swedish submarine problems. [...] The Baltic Sea area has for decades been and still is of great strategic significance for the USA and NATO. If such serious matter occurs as submarine intrusions into the waters of the neutral Sweden in this very sensitive area, and Soviet Union/Russia is believed to be responsible for these intrusions, shouldn’t the Americans in that case be interested in what has happened or still is happening. In practical terms, this would be a forwarding of the positions of the other military bloc. But the U.S. has never been concerned about the submarine issue. Isn’t that strange? Particularly since the U.S. and NATO have been covering and still cover the Baltic Sea area with satellites, aircraft, and other advanced reconnaissance systems? And have an extensive intelligence activity? But they leave us with our submarine problems. Isn’t that strange?”

U.S. Director of Naval Intelligence (DNI) gave annual briefings about Soviet naval activities to the House Armed Services Committee of the US Congress. During these briefings, they never mentioned any Soviet operations in Swedish waters. Director of Naval Intelligence Rear Admiral John Butts spoke about a new Soviet destroyer in the Baltic Sea 1982 but not about operations in Swedish waters. The same goes for the DNI’s annual reviews for all 1980s. There was absolutely nothing, and the Americans would have known whether there were any Soviet submarines, because they received the Swedish information, and the U.S. hydrophone system would have picked up any Soviet activity in the Western Baltic. Furthermore, the U.S. Naval Intelligence had no reason to hide Soviet activity for the Armed Services Committee. The Committee financed the US armed services, and US Intelligence would rather exaggerate Soviet aggressiveness to justify its military buildup. We can accordingly conclude that there was no Soviet activity in Swedish waters of any significance. If there were any Soviet submarines, the Committee would have been informed.

The Committee asked about the nationality of the submarines for the 1982 incident at Muskö. Admiral Butts presented the case together with the Secretary of the Navy John Lehman, but Butts’ section on the nationality of these submarines is still classified in the Committee Report. Butts said that the submarine at Karlskrona in 1981 was a “genuine” Soviet submarine but his following comment on the submarines at Muskö in 1982 is still classified. Butts also briefed the Committee about the new Soviet submarine Project 1910 Uniform (69 meters). “This is a sort of like our US NR-1” (41 meters), Butts says. The Uniform was developed in the 1980s similar to the later Project 1851 X-Ray (40 meters), and Butts added: “There is no chance that the Soviets could have operated this sub or anything similar near the Swedish home waters”. US Director of Naval Intelligence ruled out that any such Soviet submarine could have entered Swedish waters. There were no Soviet submarines at the time that fit the size of the submarines observed in Swedish waters. In the 1980s, US and British “scholars” said that the Soviet submarine operations in Swedish waters are “one of the most important things going on in the world just now”, the most important thing “since the Berlin Crisis”, but US Naval Intelligence told the Armed Services Committee, that there was nothing. They also indicated to Swedish Defense Ministers that the submarines rather were from the West. When this became clear to Swedish scholars, we had to admit that there was either nothing or the submarines were from the West. What was still classified in Admiral Butts’ statement points to Western submarines (see below).

Left: USS 178 Monongahela and USS 26 Belknap (with USS 1082 Elmer Montgomery) in central Stockholm on 25-27 September 1982. On 26 September, a “periscope” was observed close to the ships, former Defense and Foreign Minister Sven Andersson said. Right: On 29 September, a drawing of a small gray-black submarine sail (1 meter high) further out in Stockholm harbor. The name of the observer, “Kjell Lundquist”, is blacked out.An eighth remarkable fact is the number of indications pointing to an exercise in collaboration with the “intruder”. On 29 September 1982, the Naval Base War Diary writes that an upcoming anti-submarine operation, Notvarp, with start the following day, actually is an “exercise”. Chief of Naval Base East, Rear Admiral Christer Kierkegaard, gives a high-level briefing about Notvarp and he writes: distribution of information will be “restricted”, to train the “participants and the regional staffs”. Staff officers as well as local officers were supposed to believe that this exercise was a live anti-submarine operation. The same day, at the entrance of the Stockholm harbor, an observer saw at close range how the water was “boiling”, and then a small dark-gray submarine sail (1 x 1.5 meters) surfaced for 10 seconds. The whole event took about three minutes. Two-three days earlier, there had been a US port visit in Stockholm with a cruiser USS Belknap, a frigate USS Elmer Montgomery and a depot ship Monongahela and they may have had a small submersible for security reasons (also half a year later, on 27 May 1983, during the visit of Queen Elizabeth with her ship Britannia and the Royal Navy frigate Minerva, a small “submarine sail” was observed for half a minute, half a meter above the surface, while moving in central Stockholm indicating underwater surveillance). On 26 September 1982, two observers saw a “periscope” close to the ships. The periscope, the small sail and technical evidence were evidence for a mini-submarine in the Stockholm harbor, in the very center of Stockholm, the Chairman of the 1983 Commission, Sven Andersson said. A Navy document said that the “periscope” had been seen close to USS Belknap, a few of hundred meters from the Royal Castle. On 30 September, the Naval Base states: “The object is on its way out from Stockholm”. The Naval Base War Diary states: Reconnaissance personnel were moved out to the archipelago. Special Forces were deployed to seize the submersible. A submersible possibly brought to Stockholm on a civilian ship to guarantee the security of the naval ships, was now playing enemy as a “target submarine” in an exercise with the Swedish Defense Forces. The exercise with limited distribution of information was run by Chief of Naval Base East Christer Kierkegaard. The Naval Base briefed the Chief of the Coastal Fleet Rear Admiral Bror Stefenson (former Chief of the Submarine Flotilla; and to become Chief of Defense Staff the following day). The “cover” for the exercise was to use the US Navy ships as a bait to attract Soviet submarines to go into a trap arranged by the Swedish Navy. However, the trap was set up three days after the U.S. ships had left Sweden. The Navy was planning to get something else in the net. Swedish submarines were ordered not to operate submerged inside the archipelago (this was exceptional). The Swedish Navy must have had submarines or submersibles from a friendly navy to “play the enemy”. This was an exercise where officers on a tactical level and the regional staff were to believe that the anti-submarine operation was a “real” hunt for a Soviet submarine. On 30 September, the patrol boat Mode reports about a possible Western or “West German submarine”. The Naval Base War Diary states: should be investigated inside “the operation” [inside the Navy]: “To be reported neither to the Regional Commander [Lieutenant General Bengt Leander] nor to the Chief of Defense [General Lennart Ljung].” Only a few naval officers were supposed to be in the know. The top generals knew nothing. On 1 October, military personnel on a transport boat observed a periscope (flat top) and a mast for a minute or more at close range at a speed of five knots (see drawing above), as if the submarine wanted to be detected deep inside the restricted area of Hårsfjärden, at Sweden’s Naval Base East (Muskö). Naval Base South offered their Näcken class submarines with their modern sonar to be able to reveal the intruder’s identity, but the Muskö Chief of Staff Commander Lars-Erik Hoff rejected the offer. They were not supposed to know. Chief of Defense Staff Admiral Stefenson ordered Navy Press Officer, Commander Sven Carlsson, to prepare for a press center for up to 500 journalists. In Sweden, this implied a global event with U.S. and UK TV-channels. Soon ABC, NBC, CBS, The New York Times, Washington Post, Times, and Stern turned up. Already after the first observation of a periscope, Admiral Stefenson prepared for head-line news all over the world. How could he know that this first observation would turn into the most dramatic submarine hunt in post-War Europe with the global TV-channels having a ringside seat? On the evening on October 4, Stefenson calls Carlsson from the reception with the foreign attachés (certainly with the U.S. and the British attachés) telling him to start the press center at midnight, as if everything had been coordinated with the “intruder”. One month earlier, Carl Bildt had written in Svenska Dagbladet that Western submarines may conduct “counter-operations” in Swedish waters. Admiral Kierkegaard stated explicitly that the “intruder” was part of an “exercise” and the behavior of Admiral Kierkegaard and Admiral Stefenson largely indicate an exercise run by a foreign “intruder” together with the Naval Base, an exercise that went very, very wrong. This does not indicate a Soviet operation.

[This article is using material from the chapter 2 of my Swedish book Det svenska ubåtskriget (The Swedish Submarine War), Medströms publishing house, Stockholm, 2019. References will be found in my Swedish book and only a few links are added in the text].