The Submarine War against Sweden: Part I

US and UK operations in the 1980s: Twelve remarkable facts

The Conservative Svenska Dagbladet on 27 April 1983 (the day after the Submarine Defense Commission press conference). Headline: “Midget submarine in Stockholm”. Text: “Six Soviet submarines including three midget submarines, operated in the Stockholm Archipelago in late September and early October last year.” Around 1 October 1982, two midget submarines entered the narrow Hårsfjärden at Naval Base East at Muskö. The artist is showing a tracked midget and its mother submarine or MOSUB. The drawing of Stockholm southern archipelago shows the believed positions for the MOSUBs and where the midgets entered Hårsfjärden at the Naval Base.[This article is using material from the chapter 2 of my Swedish book Det svenska ubåtskriget (The Swedish Submarine War), Medströms publishing house, Stockholm, 2019. References will be found in my Swedish book and only a few links are added in the text].

Introduction

The stranding of a Soviet Whiskey class submarine at Sweden’s Naval Base South in Karlskrona, in October 1981, became front-page news all over the world. It totally changed Sweden. It dominated the global media. After that, submarines started to appear deep into Swedish archipelagoes on a regular basis. In July 1982, several people had observed a small dropped-shaped vessel entering the narrow channels of the Stockholm northern archipelago. In late September and in the first two weeks of October 1982, there were hundreds of observations of sub-surface activities in Hårsfjärden close to Muskö Naval Base, at Berga Naval College, inside the Stockholm harbor, and further out at the Coastal Defense base on the Mälsten Island in Stockholm southern archipelago. This event became known as “the Hårsfjärden event”.

Both small and large submarines were observed on the surface. There was even a small submarine sail observed in Stockholm harbor. In the waters of Hårsfjärden, there were observations of a regular periscope and another mast that was followed at close range and a very thin “periscope”, there were dark objects (a dark hill) that appeared in the water, a small “round sail” and a white object, there were observations of spot lights below the surface meters from the Naval Base’s underground tunnels (for submarines and surface ships), there were submarines that were pumping out air, there were streams of bubbles, there was a physical contact with a submarine 15 meters above the bottom, there were keel prints from small submersibles on the sea-floor, there were prints from wheels and from a tracked submersible, there was a sound-recording of something going on the bottom, there were sonar contacts and IR-contacts with submarines on several occasions, there were submarines leaking oil, and the Swedish Navy was able to measure the size of the submarine with an echo sounder. There were indications of a damaged or sunken submersible and of repair work on a larger submarine damaged by a mine. There were at least 2-3 vessels in Hårsfjärden area. But where did they come from? Who was responsible for these intrusions?

26 April 1983, the Chairman of the Parliamentary Submarine Defense Commission, Sweden’s former Defense and Foreign Minister Sven Andersson, and four MPs including later Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Carl Bildt, gave a press conference: Six Warsaw Pact, in praxis Soviet submarines, including mini-subs, had entered Swedish harbors and naval bases in early October 1982. Prime Minister Olof Palme protested strongly to Moscow, and Sweden recalled its ambassador. In the morning the same day, a “small submersible” appeared in the Stockholm harbor, and the following days there were observations of submarines at Sundsvall 300 km north of Stockholm and in the Hardangerfjord in southern Norway. Sweden changed drastically. In the 1970s 5-10 % of the Swedish population viewed the Soviet Union a direct threat (Swedish Board on Psychological Defense). After the stranding of the Soviet Whiskey class submarine in 1981, this figure changed to 34 %. After the 1983 Commission this figure jumped to 42 %. The number perceiving Moscow as a threat or unfriendly increased from 27 % to 83 % in three years’ time. Many people started to believe that “the Soviets were coming”.

The new Prime Minister Olof Palme had to cancel his Common Security (1982) dialogue with Moscow, a policy that was unacceptable to President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. After these intrusions Prime Minister Palme’s initiative for East-West talks was no longer credible. His vision for Europe and the world became irrelevant when he couldn’t defend his own territory. U.S. and British experts appeared on Swedish TV explaining the Soviet activity in Swedish waters. John Moore (1984) of Jane’s Fighting Ships said: “this is one of the most important things going on in the world just now”. Lynn Hansen (1984) wrote for U.S. Secretary of Defense about submarines at “the Royal Palace” in Stockholm and the Soviet inclusion of Sweden in its war plans. Milton Leitenberg (1987) at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) wrote a book about these “first Soviet military–political initiatives against a Western European state since the Berlin crisis 1960–1961”. Gordon McCormick (1990) wrote for RAND how the Soviets “began to penetrate into the heart of Sweden’s coastal defense zones” with “an average rate of between 17 and 36 foreign operations” per year.

In the 1980s, all scholarly or political works pointed to the Soviet Union. The global media wrote about Soviet intrusions. There was no doubt, but Sweden’s Foreign Minister Lennart Bodström claimed in 1985 that there was no evidence. Defense Minister Anders Thunborg said later: “It was wrong to point to the Soviet Union”. Former Deputy Prime Minister, from 1986 Prime Minister Ingvar Carlsson wrote in 1999 that the Swedish Navy had been too confident in pointing to the Soviet Union. The Navy “had definitely arrived at the wrong conclusions”. The 1995 Submarine Commission with former Chief of Military Intelligence, Major General Bengt Wallroth, as its Secretary General, had the same view. Andersson’s State Secretary for Defense, Karl Frithiofson, said: “the submarines were from the West”. Chief of Army Lieutenant General Nils Sköld also pointed to Western submarines. Defense Minister Thage G. Peterson referred to his counterpart, US Secretary of Defense William Perry, who said in 1996 that the submarines “don’t have to be Russian”. Ambassador Rolf Ekéus’ 2001 Submarine Inquiry, with Ambassador Mathias Mossberg as its Secretary General, said that it might have been both Soviet and Western intrusions. As a former civilian expert to this Inquiry, I wrote a book in 2004 presenting evidence for U.S.-UK deception operations. The U.S. Navy was very curious and visited our website 30,000 times in 10 months. My analysis was adopted by the official Danish Cold War History Report (2005) that concluded that the submarines in Sweden were from the West. A similar view was presented by the Finnish Cold War History. Mossberg wrote a book in 2009 (with an extended version in 2016) also pointing to Western intrusions. In the 1980s, almost everyone had argued that the intruding submarines clearly were from the Soviet Union. In the 1990s, this was no longer obvious, and from the 2000s diplomats, officers and scholars started to argue that these submarines may have been from the West. There are several reasons for this change. This article is based on chapter 2 of my book: Det Svenska ubåtskriget [The Swedish Submarine War] (Stockholm: Medströms, 2019). I will bring up twelve facts that have played an important role for the changed interpretation of the submarines intruding Swedish waters in the 1980s.

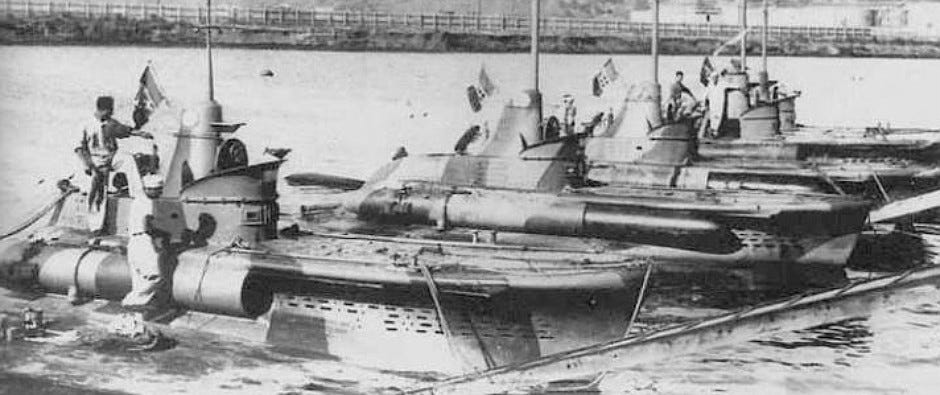

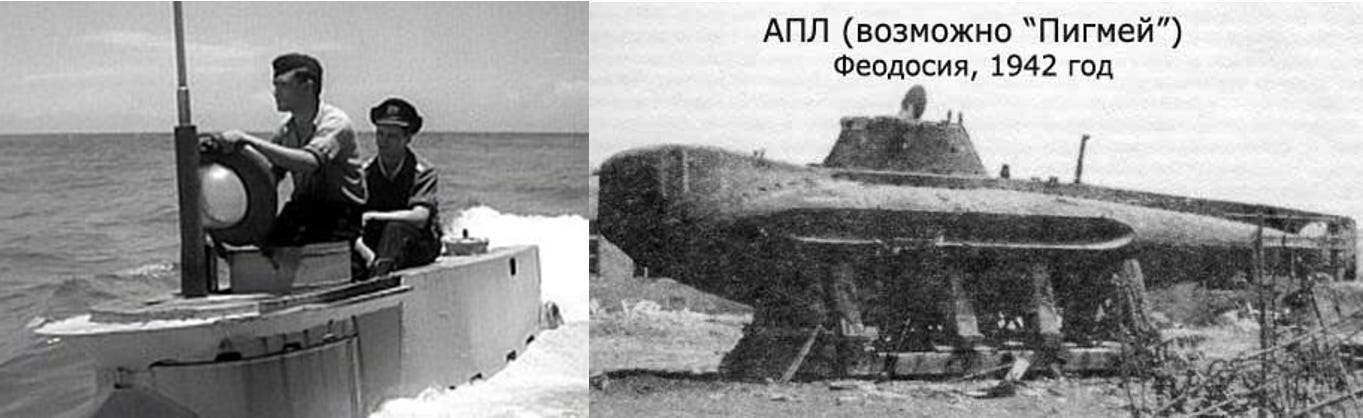

Five Italian CB submarines in the Romanian city of Constanta at the Black Sea in 1941. The Soviets captured most of these CB in 1944, but they were scraped in 1945. The Soviet Union kept none of them.A first remarkable fact is that the Soviets do not seem to have had the capabilities for these very ambitious operations that were conducted deep into Swedish archipelagoes, harbors, and naval bases. In the 1980s, some British and U.S. scholars like McCormick and Compton-Hall claimed that the Soviets had a large number or 200 military midget submarines, but now many years afterwards we still don’t have the evidence for any Soviet 20-30 meters’ vessels until the end of the 1980s (one Pyranja in 1989 and one in 1990), and we only have confirmation of very few 10-15 meters’ dry vessels. The Soviet Baltic Fleet may have had less than a handful of these latter vessels, and they were not developed for offensive operations. In 1952, the British Director of Naval Intelligence wrote that “the Russians had acquired some 50-70 ex-German, Italian and Japanese midget submarines”, while in 1953 a CIA document claimed that the Soviets had “about 20 of the ex-German Seehund type and about 50 of the Soviet type. The Soviet midget submarines constructed after 1947 were an improvement of the previous type and made use of the German Seehund plans”. However, H.I. Sutton writes that only two Seehund (12 meters) were brought to Russia and only one was “brought back into limited service for trial purposes in 1948”. The Soviets also captured 4-5 Italian CB- submarines (15 meters) in the Black Sea in 1944. They were all scrapped in 1945. The Soviets developed their own two Pigmei midgets (16 meters) in 1935-36, but they never became operational. Different from above British and US intelligence estimates claiming 50-70 Soviet midget submarines, in early 1950s, there were most likely none. In the 1950s and 1960s, there was probably no Soviet midget submarine.

H.I. Sutton compares the US and British midget submarine estimates with the “Bomber gap” in mid-1950s, when 20 Soviet Bison strategic bombers were estimated to be 800 bombers by 1960, and the “Missile gap”, when the 1958 US National Intelligence Estimate wrote that the Soviet Union would have about 500 Inter-Continental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) by 1962 (a Pentagon estimate arrived to about “1000”), when the actual number after the U-2 and satellite reconnaissance was found to be “four”. And different from these forces, midget submarines were never a Soviet priority. The Soviet Navy built a large number of small coastal submarines after World War II and up to the 1960s. They built 58 Project 96 (50 meters) and from early 1950s they built 30 Project A615 (Quebec, 57 meters) and 236 of the larger coastal submarine Project 613 (Whiskey, 76 meters), but they built no midgets.

In the mid-1960s, the Soviets worried increasingly about harbor security and saw an urgent need to defend against Western naval Special Force attacks. A Soviet Navy document from 1965, acquired by the CIA, points to a Soviet demand for base defenses, which would have demanded some small vessels to test their own defenses, but not until the 1970s and early 1980s did the Soviet Navy build a few small “dry vessels” (dry interior), where the divers could stay warm during the transport. These submersibles were developed for sea-floor engineering and recovery operations like the Project 1837 (12 meters) and Project 1839 (13.5 meters), and nine submersibles were tasked to test harbor security: SPLTs Project 1015 (15-16 meters). The latter vessels were used as “target submarines” during anti-submarine exercises. From 1970, the Soviets also introduced a few “wet submersibles” (flooded interior), where divers would stay in the cold water and use their scuba tanks for breathing. These were the two-men Project 907 Triton 1 (5 meters) and from 1975 also the six-men Project 908 Triton 2 (9.5 meters).

Left: German Seehund (12 meters) during World War II. Right: photo of the Soviet Pigmei or Проект АПЛ (16 meters) from 1942 (built in 1936). During World War II, the Germans built 285 Seehund, and 324 and 393 of the less successful Biber (9 meters) and Molch (11 meters), while the Soviets had built two Pigmei that never became operational. The Soviets never prioritized midget submarines. The Baltic Sea had two SPLTs (15 meters) used for testing the readiness of Soviet coastal defenses from 1970s.An Italian-built COSMOS (23 meters) from early 1970s with a white-painted SDV (Swimmer Delivery Vehicle) on each side (Photo published in 1974).In 1982, the Baltic Fleet allegedly had two SPLTs (one in Kronstadt and one in Baltijsk), 5-10 Triton 1 and perhaps two Triton 2. Hypothetically, these vessels could have been used for offensive operations, but the Triton vessels could only operate in the cold water of the Baltics for a few hours. Their capabilities were very limited and could not have been used for the extended operations in Swedish waters. Most of these submersibles were brought to target area on Mother Ships (MOSHIPs), while the Project 1837 could also have been brought on a Mother Submarine (MOSUB), Project 940 (India class or in Russian “Lenok”), but in the 1980s the Project 940 was never in the Baltic (Danish Intelligence). These small Soviet vessels could not explain the operations into Swedish naval bases and harbors that similar to the Hårsfjärden incident went on for a week or more. Such operations would have presupposed the use of offensive dry vessels that the Soviets at the time did not have. Except for possibly the SPLTs, the Soviets did not have any capabilities for the very complex operations conducted deep into Swedish archipelagoes.

During the Cold War, nobody outside the intelligence community knew what kind of vessels the Soviets had. Scholars could imagine that they had secret classes of midget submarines. Carl Bildt, for example, argued in 1990 that there were “two classes of secret Soviet midget submarines” (described as the “Type 1” and the “Type 2”). Now, some 30 years afterwards, we have found no indication of these Soviet capabilities. The Soviets did not receive an offensive midget until the end of the Cold War in 1989 – the Pyranja (28 meters) – which was able to carry two wet Sirena (9 meters). This design, however, was not successful. The two Pyranja were decommissioned already in 1996. In contrast, Italy, Germany, and Britain produced a large number of small Special Force submarines during or shortly after World War II. The Germans built as many as 285 Seehund (12 meters) and many other small vessels. The British built 36 X or XE class midgets (15-16 meters) and the Italians built 25 CA and CB class midgets. They also built many midgets with offensive capabilities in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s (see below). The fact that these Western states had a long experience of building midgets and mini-submarines and that COSMOS in Italy had built tens of 20-30 meters’ submarines during these years, while the Soviets built none, indicates that we rather should look for the “culprit” for the Swedish intrusions in the West. When Western scholars became aware of the real “midget submarine gap”, it appeared increasingly unlikely that the successful mini-submarine operations in Swedish waters would have been run by the Soviet Union. We had to look at Western alternatives.

Left: Swedish 1983 Submarine Defense Commission Report for which Carl Bildt played an important role. The now declassified drawing of a periscope and a mast moving at a speed of 5 knots, visible for five minutes in Hårsfjärden on 1 October 1982. Swedish 1995 Commission Report (“Ubåtsfrågan 1981-1994). Right: the Submarine Inquiry Report of 2001. Left: Secretary General of the 2001 Submarine Inquiry, Ambassador Mathias Mossberg, and the Head of the Inquiry Ambassador Rolf Ekéus. Right: Admiral Kjell Prytz, Chief of Navy in Norway (1992-95).A second remarkable fact is that the intruding submarines in the 1980s turned out to have shown sails and periscopes inside Swedish archipelagoes, sometimes even inside harbors and naval bases in total conflict with Soviet interests. A submarine operating in enemy waters is supposed to raise its periscope just centimeters above the surface and not for more than a few seconds to avoid detection. A submarine sail should never be made visible. From early 1980s, however, there were observations of submarines and smaller submersibles on the surface inside Swedish archipelagoes on a regular basis. The first sighting of a submarine in Hårsfjärden in 1982 was a periscope and another mast (see the original drawing above).

A conscript on a transport boat described “two dark pipes (height 3 dm, flat top, diameter about 10 cm, mutual distance 1–1.5 meters) course Berganäs. [This observer sees the pipes for] about 1 min. After this, the pipes turn towards Kärringholmen. Both [he and his colleague] estimate the speed at about 5 knots.”

But that a Soviet submarine should demonstrate its presence in this way next to a foreign naval base is completely unreasonable. Why would the Soviets try to launch a submarine hunt for their own submarine deep into Swedish waters? In 1983, Defense Minister Anders Thunborg established a direct telephone line between the Minister himself and the Naval Staff for the “daily reports” on the submerine intrusions. The 1995 Submarine Commission writes: in 1981-1990 there were 2,144 observations of “objects”, suspected submarines incl. sails and periscopes. There were 352 observations later identified as “certain” or “probable” (almost certain) submarine and 1421 observations identified as “possible submarine”, which includes supposed “submarines” seen by naval officers. In addition, there were close to a hundred reports about divers, some using Swimmer Delivery Vehicles (SDVs). The 1995 Commission wrote that dozens of small vessels had been reported to turn up close to sailing boats or fishing boats at a distance of less than 10 meters. Several hundred observations of midget- or mini-submarines were made at a distance of less than 100 meters. Observers even described details of the hull.

Some academics argued that it was all about a hysterical population having too much fantasy, but later Norwegian Chief of Navy Rear Admiral Kjell Prytz made a test, letting Norwegian submarines show periscopes along the Norwegian coast and Commodore Roald Gjelsten (Oslo: Institute for Defense Studies, 2018) made a study of these observations. The coastal community had been remarkably correct. The majority or 53% of all observations reported by fishermen and others were “certain submarines”, because they actually referred to Norwegian or known allied submarines. Some observations might possibly have referred to Soviet submarines, but Prytz states in Norway’s “Defense History 1970-2000” (Børresen et.al., 2004) that British and US submarines might have been “given the task to show up along the Norwegian coast” to make the Norwegians more alert. Prytz and Gjelsten concluded: the reports from the coastal community were largely credible. And in Sweden, the way submarines demonstrated their periscope and sail didn’t make sense if you wanted to operate covertly. The Swedish Navy let their own submarine HMS Sjöhästen test Swedish military personnel by showing its periscope in a professional way a number of times within a limited area, where the observers were looking for it. The Sjöhästen was able to use its periscope 88 times before any observer was able to spot it. On a second exercise, the submarine showed periscope or other masts 184 times before anyone was able to see it (Svensson, 2005). If a sub wants to avoid detection, it is almost impossible to detect it visually, but in Sweden, in the 1980s, submarines appeared on the surface on a regular basis inside the most sensitive naval bases and inside the Stockholm harbor. Commander Hans von Hofsten (1993) describes how submarines in 1980 had played cat and mouse with the destroyer Halland both at Karlskrona and at Utö in Stockholm Archipelago, while testing Swedish capabilities. On the first occasion, US Naval Attaché Captain Smetherham was the guest onboard. The event gave him the ability to study the Swedish capability to pursue an intruder.

Later Chief of the Submarine Division Nils Bruzelius wrote the Swedish Naval journal (1982):

“The question we have to answer is the following: why are the foreign submarines so easily discovered, when Swedish submarines, under the same circumstances (in Swedish waters), are almost never discovered? The reason cannot be that these foreign submarine crews are badly trained. On the contrary, they have proved to be very capable when targeted by advanced anti-submarine warfare. The only explanation I can find is quite simply that ‘they are discovered because they want to be’”.

The submarines rather seemed to test Swedish naval base security by provoking Swedish anti-submarine operations. To surface in the restricted area of Muskö Naval Base and inside Stockholm harbor is totally inconsistent with Soviet interests. These operations were not consistent with Soviet activities in Swedish waters. Or rather, the way the submarines operated seemed to exclude Soviet activity. Apparently, someone tried to test the Swedes by making them aware of the threat. Scholars had to think in terms of operations conducted by Western powers demonstrating their presence: “to almost surface in the Stockholm harbor [to show] how far could we get without you being aware of it”. This is the explanation British Navy Minister Keith Speed gave on Swedish TV for the British operations in Swedish waters.

Original drawings made by the divers from left: “transponder” no. 1 (30 cm long, 10 cm in diameter) attached to a 40 cm concrete plate. The second drawing shows “Mik 5” (hydrophone no. 5), “Föremål 1” (object no. 1) and “Föremål 2” (object no. 2) and “spår” (prints) with tracked prints (15 meters) and a keel print (20 meters). Right: Drawing of the U.S. submersible Deep Quest showing how it uses transponders for navigation.From the video film with the “transponder” no. 1. Drawing of “Transponder” no. 2 and a US TrackLink transponder.A third remarkable fact is the disappearance of definitive evidence. We know about evidence that would have made it possible for us to prove the nationality of the submarines, but this evidence has disappeared. Perfectly sharp photos of “Type 1” (10 meters) and “Type 2” submarines (20-30 meters), which would have made it possible to identify the single submarines, just disappeared. The 2001 Inquiry found that oil samples as well as samples and photos of a green Visual Distress Signal (VDS) had disappeared from the archives. This material would have made it possible to identify the nationality of the intruder. Most important pages from the Defense Staff War Diary had disappeared from the archive, both in the hand-written and the printed-out version. Objects found on the sea floor that would reveal the nationality just disappeared. We know that 24 KHz signals were picked up by the five hydrophones at Mälsten Costal Defense base in the autumn 1982. The signals indicated a “transponder” on the bottom, which, for example, could give the position for the midgets where to meet their MOSUB. The speed of sound in water in the area was known (1.43 meter per millisecond), which made Tore Pentelius of Swedish Defense Material (FMV) able to calculate the exact position of the object sending the signals. The object was located to 1 km southeast of Mälsten (25-30 meters southeast of hydrophone no. 5). Rolf Andersson from FMV, who was responsible for picking up signals, went on a boat to the position of the transmitter together with later Chief of Navy Dick Börjesson, Chief of the Divers Kent Pejdell and a couple of his divers. The divers went down and found a 30 cm long cylindrical object (10 cm in diameter) attached to a 40 cm wide concrete plate. The object looked exactly like a transponder. The divers made a drawing and a video film. At this very position, the divers also found prints on the sea floor from what they believed were two midgets and one larger submarine believed to be a MOSUB, as if the transponder signals had given them the position where to meet. Their meeting actually presupposed signals from most likely a transponder. On 6 December 1982, Chief of Defense Lennart Ljung wrote in his diary that he had been informed by Chief of Navy Per Rudberg:

“[T]he position of the transmitter has been located […] CM [Per Rudberg] now reports that they have found an object at the given position that might be a transmitter-receiver of some kind. It is still on the bottom and is relatively small and might be a transponder. [… I]f it will turn out that this is a kind of transmitter, it will be a sensation, and it could make the submarine affair appear as something very different. One should not exclude, or rather it is quite probable that if one finds transponders, one would most likely also be able to identify the intruder. This will accordingly be extremely sensitive politically.”

General Ljung informed Prime Minister Palme on 14 December. A later document stated that the first object had been brought up and another object had been found close to the first one. A drawing indicates another transponder, 30 cm long (the thick part was 20 cm) with a diameter of 15 cm (similar to the US TrackLink transponder above). Afterwards, there was total silence. Vice Admiral Rudberg could not explain this. If these had been Soviet “transponders”, they would have been put before the global media at the press conference. Chief of Intelligence of the Defense Research Establishment (FOA), Bengt Odin, said that if this object had come from the Soviet Union, he would have received it. One would not have kept this secret to us, he said. The silence rather indicates that it was “politically sensitive”. The object might have been from a Western country, he said. All real evidence (photos, samples, objects, or vital documents) was kept secret also to the 2001 Submarine Inquiry, despite the fact that Prime Minister Göran Persson had ordered the Defense Forces to show all its evidence. The only reason for the definite evidence hidden from the Inquiry was that the evidence was not consistent with Soviet intrusions.

The Mälsten hydrophone from 1982 (photo Rolf Andersson). The drawing (from the Navy Sea-floor investigation, attachment 9) shows “Mik 4” and “Mik 5” (hydrophone no. 4 and 5), and “x” (“Tidigare bärgat föremål nr 1 [already recovered object no. 1]) 25-30 meters southeast of Mik 5 and “x” (“Föremål nr 2” [object no. 2]).A fourth remarkable fact is how far some Swedish Navy officers were willing to go in order to cover up real physical evidence. The transponder mentioned above was located by triangulating the 24 KHz signals received by the five hydrophones at Mälsten. The exact position was pinpointed by FMV. The object looking like a transponder attached to a concrete plate was found in this very position. At this place, there were also prints on the sea-floor from three vessels. The Sea-floor Inquiry wrote that a midget had “been meeting or been docking on the larger submarine” at this very position, which almost certainly pre-supposed the use of a transponder. Otherwise, they would not have been able to meet. However, the Military Expert to the Submarine Inquiry, Rear Admiral Göran Wallén, claimed that the transponder could have been an “artillery shell”. During the TV interview, Swedish journalist Lars Borgnäs showed him a drawing of the transponder sitting on a concrete plate, and asked him: “does this look like an artillery shell?” Admiral Wallén responded: “There are many kinds of artillery shells. This could be one they have made an experiment with”. But artillery shells are not attached to concrete plates, and they don’t send signals. He argued that the signals were not from a transponder but were “found to originate from Mälsten’s power grid”. But a power grid does not send signals, Rolf Andersson said. Wallén did not even try to come up with a technically plausible explanation.

Another Navy officer argued that the transponder actually was hydrophone no. 5. The hydrophone was positioned one meter above the bottom and attached with nylon lines to an anchor below and to buoy above it. A leak in the buoy would have made it lie down on its anchor, which was a “concrete plate”, he said. The transponder was nothing but the navy’s own hydrophone. This was all about Winnie-the-Pooh and Piglet pursuing their own footprints. This may appear to be a more realistic explanation, but it all turned out to be a bluff. Firstly, the divers had found the cylindrical object 25-30 meters southeast of hydrophone no-5 (see the map above). The transponder was not a hydrophone. Secondly, the dimensions of the hydrophone were 50 cm long and 7 cm in diameter (see photo above), while the dimensions of the transponder were 30 cm long and 10 cm in diameter. From looking at the video film and the drawing, it is obvious that this is not the same object. Thirdly, the anchor to the hydrophone was not a “concrete plate”. Rolf Andersson, who deployed this system, said that the anchor was a heavy iron ball (25 or 50 kilos). Fourthly, the buoy to the hydrophone had not been leaking. The naval officer above argued that the hydrophone had collapsed, because of a leak in the buoy in the night to 14 October. This had made the fuse to the hydrophone blow, he said, but the sound recording show that there was a noise with very high decibel close to the hydrophones (sounds like a tracked vessel moving on the ground) just before the fuse blew and the hydrophone functioned again after the fused had been changed. This would not have happened if the hydrophone had been lying on the bottom. It was the noise, not “a collapse of the buoy” that made the fuse blow. If the transponder had been lying on the bottom, the fuse would blow again and again. Fifthly, who was then sending the signals of 24 KHz? One has to ask oneself: why did these responsible officers present obviously false information? The most likely explanation is that this physical evidence was not consistent with a Soviet operation. It did not point to the Soviets but to the West.

Also, evidence for a tape-recording of a certain submarine was covered up. It was exchanged with a tape-recording of a civilian surface ship and claimed to be “evidence for a Soviet submarine”. After the sonar operator at Mälsten had tape-recorded a “certain submarine” at 18:00 on 12 October 1982, Chief of Staff Vice Admiral Bror Stefenson went home to Chief of Navy Vice Admiral Per Rudberg, and at 21:00 he walked over to the apartment of Chief of Defense General Ljung. They both went to the Defense Staff. A recording of a submarine was important, and it could also make it possible to identify the intruder, which would be “extremely sensitive politically”. General Ljung returned home at 23:00, while Stefenson stayed at the Defense Staff to handle the situation. The 20-minutes’ long tape-recording at 18:00 was, however, exchanged with a 3.47-minute tape-recording of a propeller sound from a surface vessel at around 14:30. The rotations per minute (rpm) for the latter recording were seemingly consistent with a Soviet Project 613 (Whiskey class submarine). The Swedish Navy Analysis Group (MAna) claimed that they had tape-recorded a Soviet submarine, and this recording was presented as “definitive evidence” to the 1983 Submarine Defense Commission, but the 1995 Submarine Commission argued that it was not possible to point to any specific state. As a Civilian Expert to the 2001 Submarine Inquiry, I found that this latter recording was not the recording of a “certain submarine” at 18:00. It had been made hours earlier on the same tape and the sonar operator did not recognize it. In 2008, it turned out that this recording almost certainly originated from a taxi boat Amalia at about 14:30 (with a Dagens Nyheter journalist and a photographer). The recording of a “certain submarine” at 18:00 pointed to a submarine with very silent propellers, which rather would indicate a Western submarine. The 1995 Commission also showed that other sounds described as evidence for Soviet submarines in late 1980s and early 1990s turned out to have biological origin (mink and herring). No recording of submarine sounds pointed to the Soviet Union.