The Deception Committee: Part I

How the CIA and the US Navy deceived the Swedes in the 1980s

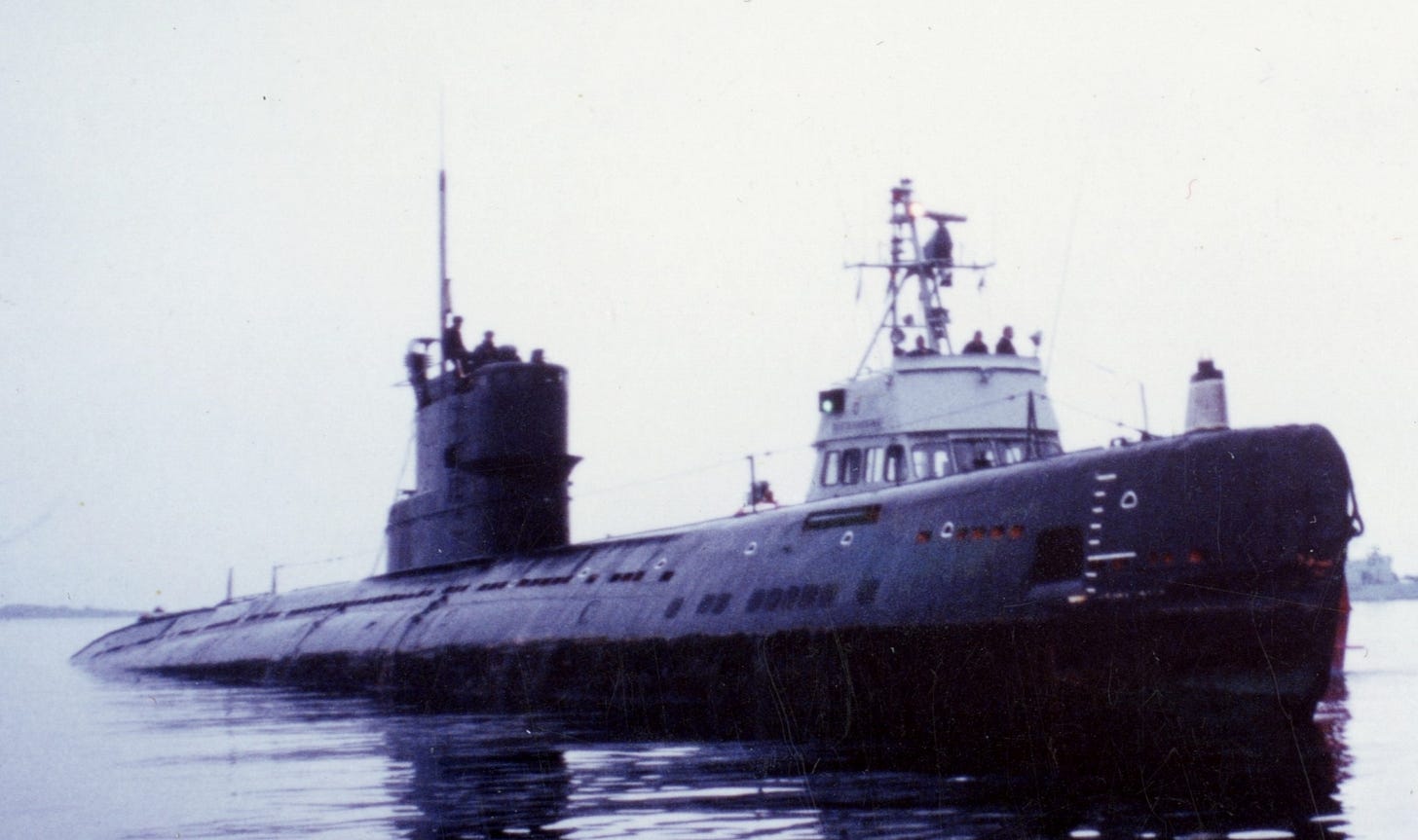

In October 1981, a Soviet Whiskey-class submarine S-363 – in Western media called “Whiskey on the Rocks” – stranded on an island in the Swedish archipelago at the Naval Base South in Karlskrona (photo: Marinmuseum, Karlskrona). Some people believed it was a navigational mistake, others including the official Sweden believed it was an espionage or training operation deep into the Swedish fjord, but why would the Russians go with a submarine on the surface for espionage in a fjord that is so shallow that you couldn’t dive and so narrow that you had difficulty to turn around? On the other hand, how were they able to hit the extremely narrow entrance of the fjord in darkness and then, at this very moment, turn to 30 degrees, which was the course of the narrow fjord? When the submarine stranded on the beach to a small island, why did it run its propeller forward (the divers found an embankment of gravel behind the propellers) as if it wanted to get higher up on the beach? Why had the U.S. naval attachés arrived in Karlskrona at the very time of the stranding – already 12 hours before any Swede supposedly knew about it? Why did the two attachés appear at the Naval Base meeting the Chief of the Naval Base Lennart Forsman early in the morning, in darkness before regular working hours and before the submarine had been spotted by any Swede? Why was the Naval Base’s Chief of Staff Karl Andersson not pre-notified about the upcoming high-level visit as he was every time before and after this incident? On the last day, the submarine was navigated and commanded, not by the young captain of the submarine and not by his regular navigation officer but by a senior officer, who took over the command at a crucial moment. Why did this senior officer interrupt the captain's order to dive under the presumed “NATO destroyer” (which actually was the harbor lights from a small island) and order him to avoid the “destroyer” on the surface by turning to 30 degrees, the course of the narrow fjord? Why was the Chief of Staff Karl Andersson, who was responsible for questioning members of the crew, ordered not to question this senior navigation officer, the only officer onboard who really knew what had happened? And why did the Chief of the Naval Base Forsman, who gave this remarkable order and who was a former Swedish naval attaché to Washington and a friend of the two new U.S. attachés in Stockholm, hide in his office, while letting Andersson appear before the global media? The stranded submarine certainly was a test of Swedish preparedness. Sweden changed drastically and became a different country, now hostile to the Soviets.[This article is using material from the chapter 3 of my Swedish book Det svenska ubåtskriget (The Swedish Submarine War), Medströms Publishing House, Stockholm, 2019. References will be found in my Swedish book and only a few links are added in the text. The caption under the above photo of “the Whiskey on the Rocks” is from my Swedish book Navigationsexperten (The Navigation Expert), Karneval Publishing House, Stockholm, 2021. Some quotes are from the German-French TV channels Arte and ZDF and from Swedish TV channel SVT: Some of the later quotes can be find in my 2012 article “Subs and PSYOPs: The 1982 Submarine Intrusions”, Intelligence and National Security.]

Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger from SVT’s interview on 7 March 2000. Weinberger is saying that there were no Western intrusions without consultations with the Swedes (navy-to-navy). And [these intrusions were] in the interest of both Sweden and NATO that this was doneBritish Navy Minister Keith Speed in the SVT interview on 11 April 2000 saying that the British could possibly use submarines to almost surface in the Stockholm harbor. Not quite, but that sort of thing. How far could we get without you being aware of it?Statements by senior officials

In March 2000, US former Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger stated in a long interview on SVT (Swedish TV) that during his term in office (1981-87), the U.S. had operated Western submarines in Swedish waters frequently and regularly to test Swedish coastal defenses. A month later, British Navy Minister Keith Speed said the same. From time to time, we had to test the Swedish coastal defenses, they said. From 1982, small submarines turned up in Swedish archipelagoes, harbors and naval bases showing their periscopes, sometimes even their sails. In Sweden and in Europe as a whole, almost everyone believed that these were Soviet submarines. The Soviet Union was considered to be the enemy and “the Whiskey on the Rocks” in 1981 (photo above) was definitely a Soviet submarine. One journalist with good military sources wrote in a book in 1984 that the submarines were from the West. Some senior military officers indicated the same, and in 1983 a former Swedish state secretary for defense Karl Frithiofson told his son that these submarines had been from the West. The Soviet leaders wondered why the Swedish admirals tried to limit the use of force. The Soviet leader Yuri Andropov urged the Swedes to sink every intruding submarine, so the Swedes could see themselves who is responsible. It is not our submarines, he said, but more than 99 % of the media and the government officials took for granted that the submarines were from the Soviet Union. One could not imagine that these were Western submarines. In 1983, Sweden protested strongly against the Soviet intrusions. In three years, the number of Swedes regarding the Soviet Union as hostile or a threat changed from 25-30 percent to 83 percent.

Left: U.S. Navy Secretary John F. Lehman at the Arte-interview in 2009. Right: Secretary Lehman and the author, Bodø Maritime Strategy Conference in 2007. John Lehman is well-dressed, because he is going to give the speech at the dinner after our trip on Vestfjord, where Lehman’s aircraft carriers were supposed to seek protection in a war.At a conference in 2007, I asked Caspar Weinberger’s Secretary of the Navy John Lehman, who had taken the decision about the operations in Swedish waters that Weinberger had spoken about on Swedish TV. John Lehman said that these operations in Swedish waters had been decided by a “Deception Operation Committee” under Chairmanship of the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) William Casey. This interagency committee also included the Special Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs (the national security advisor) Dick Allen, and one representative from the State Department and one from Defense. This committee had taken the decision about the Swedish operations, Lehman said. He could have avoided my question. He could have said: “I don’t know what you are talking about?” But he didn’t. He named the committee and the people involved. In 2009, Lehman told the TV channel Arte:

“[D]uring the transition [of the Reagan Team Nov. 1980 - Jan. 1981], Bill Casey, who became the Director of the CIA, convinced President Elect Reagan that in addition to the big military buildup, that he [Reagan] had already been committed to and agreed to, there should be a major effort with what some came to call the ‘Deception Committee’. We would build NATO military capability to be 10 feet tall. The use of deception could make it appear to the Soviets to be 20 feet tall. And really Star Wars came out of that Deception Committee originally. Casey was part of the OSS and very much involved in the operation to deceive the Nazi General Staff. [… The U.S.] had General Patton with a fake headquarters, and they convinced the Nazi General Staff that there was a whole additional army that they didn’t have […] Casey was very much involved in this and recognized that you could use deception very effectively and particularly if you have a paranoid enemy [like the Soviets…] Some of [the deception operations have] still not been declassified. [One was] should we say, close to the Soviet Union [using] this deep diving submarine Alvin. [Arte continued: ‘Talking about the flanks. We have the Swedish submarine crises there. Caspar Weinberger acknowledged that American submarines or at least Western submarines had been in Swedish waters. Was that also part of the deception against the Soviets?’] I cannot say at this point whether it was intentional or not, but we did want the Soviets to know that we could do things in places that they didn’t think we could. And we didn’t want them to learn too much obviously […] Yet tweak their paranoia by showing a little bit of our ankle, so they would say: ‘Wow, if they are doing that, what else might they be doing’, making them feel vulnerable. I know that Secretary Weinberger would seem to [have] acknowledged something. I wouldn’t disagree with him, but you know I better not comment upon it. [Arte: ‘In this case, a submarine was damaged. Did that send shockwaves to the US Navy?’] Well, the short answer is No.”

According to Secretary Lehman, the Deception Committee was as significant for “winning the Cold War” as the military buildup with his 600 Ship Navy. The “Deception Committee” operations using small submarines “should we say close to the Soviet Union” are still classified, Lehman said, and he indirectly confirmed their Swedish operations. He also told me and others explicitly that the U.S. had been running these operations. Lehman didn’t disagree with what Weinberger had said about U.S. or Western operations in Swedish waters, but he pointed to their indirect implications for the Soviets. The intrusions into Swedish waters did not just persuade Swedish and European political leaders from collaborating with Moscow, these intrusions also made a paranoid Soviet leadership worry about what else the U.S. might be doing “making them feel vulnerable” or perhaps the Soviets would also worry about the loyalty of their own forces. The operations in Swedish waters were indirectly targeting the Soviet Union. Lehman’s Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger told Swedish SVT in 2000 that the U.S. had operated submarines “regularly” and “frequently” in Swedish waters after Navy-to-Navy consultations. Weinberger said:

“[The Swedish-US consultations were] Navy-to-Navy, the US Navy to the Swedish Navy, I believe. The Swedish Navy is part of the Swedish Government, and the US Navy is part of the US Government. Responsible officials on both sides would have discussions, consultations and agreements would flow from that to make sure that they get all help needed to protect their sovereignty of their waters. If for example Sweden [the Swedish Navy representative] would have said that you must not have any intrusions of that area in this month that would certainly have been honored and respected by NATO …]. What I am saying is that at no time, to my knowledge, did NATO simply send a submarine directly into Swedish waters without consultations and prior discussions and agreements that that could be done. Under those circumstances, it was not a pressing problem. It was part of a routine regular scheduled series of defense testing that NATO did and indeed had to do to be responsible and liable. [… The “Whiskey on the Rocks”] was a clear violation, and submarines can get in where they are not wanted, and that is exactly why we made this defensive testing and these defensive maneuvers to assure that they would not be able to do that without being detected. That particular submarine [the Whiskey on the Rocks] was quite visible to everybody, and it was exactly the kind of thing that NATO was trying to test the defenses to not permit it to happen. It was very much in Sweden’s interest that that would not happen. […] Besides that, one intrusion of the Whiskey-class submarine, there were no violations, no capabilities of the Soviets to make an attack that could not be defended against, and that was the mission of NATO, and it required the cooperation of many countries. […] The point was that it was necessary to test frequently the capabilities of all countries, not only in the Baltic – which is very strategic, of course – but in the Mediterranean and Asiatic waters and all the rest. [SVT: How frequently was it done in Sweden?] I don’t know. Enough, to comply with the military requirements for making sure that they were up to date. We would know when the Soviets acquired a new kind of submarine. We would then have to see if our defenses were adequate against that. And all this was done on a regular basis, and on an agreed upon basis.”

British Navy Minister Keith Speed confirmed Weinberger’s statement. He told Swedish TV:

“When I was a Navy Minister nineteen years ago, the sort of things Mr. Weinberger was describing was the sort of things that I would expect the British Government to [make] happen; indeed, in my very own small way, I was enabling it to happen too. In other words, we were not doing this sort of testing of other countries’ defenses or training, call it what you will, without the overall agreement of both parties. [… Swedish TV: “But the testing was conducted in Sweden. That you are confirming?” Speed: “Yes”. Swedish TV: “You are confirming that?” Speed: “Yes” ...] If something happens like the “Whiskey on the Rocks”, it wouldn’t be a very good idea to have a British submarine to make an exercise ten days after the “Whiskey on the Rocks” in 1981. It would have been politically sensitive. Let’s relax. Perhaps think about it in a few months’ time. It’s common sense. [...] We would not necessarily say that we would be precisely here. Because if we told them that, and if we were trying to probe or test your defenses, it wouldn’t have been very sensible neither from your point of view nor from ours. […] There might well be penetration [type] exercises. Can submarines actually get in and almost surface in the Stockholm harbor? Not quite, but that sort of thing. How far could we get without you being aware of it? [...] As a Navy Minister I was aware of these trainings.”

Keith Speed said that they had used very silent diesel-electric Oberon and Porpoise class submarines for these Baltic Sea operations, and at least one Porpoise class, HMS Porpoise, was rebuilt for carrying midget submarines for deep penetration of coastal areas in the Baltic Sea. One Royal Navy submarine captain told me that HMS Porpoise had been used for operations in Swedish waters. The U.S. and UK tests were supposedly made deep into Swedish waters, which would increase the Swedish awareness of the Soviet enemy, and “as long as somebody in the High Command in Stockholm was aware that there was going to be some intrusions during a given period”, it was OK, said the spokesperson for Jane’s Fighting Ships Paul Beaver to SVT.

Left: Royal Navy’s HMS Porpoise (88 meters) was a Mother Submarine (MOSUB) rebuilt to carry two submersibles probably in 1979 (photo from the last journey of the Porpoise in 1985). A number of pipes to external tanks were added inside the outer hull to calibrate the weight of the submarine when carrying its two submersibles while entering the “freshwater sea” of the Baltic. The Porpoise has a typical white front of the sail to make it easier for the submersibles to find her exact position under the water. She was put on the disposal list in 1983 and sank in 1985. Right: The U.S. USS Cavalla (92 meters) with a DSRV (Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicle; 15 meters) on its back and with a similar white front of the sail (Photo: U.S. Navy). The DSRVs were used primarily for intelligence. The “R” also stands for “research” meaning "intelligence". Also other DSRV carriers had a white front of the sail.Eight years later Pelle Neroth at Sunday Times asked Keith Speed if he could confirm once again that these operations were run into Swedish waters. He said: “Yes, but I cannot say any more as I am bound by the Official Secrets Act until the day I die”. Secretary Weinberger spoke about “NATO”, but he also spoke about Navy-to-Navy consultations, which means that the operations rather were run as state-to-state operations. Sunday Times asked Keith Speed if he had “informed the Swedish Government. Any minister?” Speed responded: “No, it was a Navy-to-Navy issue. The [British] Chief of Defense Staff or the Flag Officer Submarines told his Swedish counterpart, and it was up to them to inform their government.” Sunday Times continued: “Did they do so?” and Speed replied: “That was their business. I don’t know.” The consultations were run Navy-to-Navy.

When Caspar Weinberger spoke about “NATO”, he did not mean NATO as a formal organization, but rather U.S. or UK operations in cooperation with one or more allies, I was told by former Chairman of the NATO Military Committee (1989-93), General Vigleik Eide. Eide read the manuscript for my book, The Secret War against Sweden (Frank Cass 2004), where I had outlined the U.S. and British operations. To run these operations within the NATO system was too sensitive, he said. NATO Secretary General George Robertson visited Sweden three weeks after the Weinberger interview. He had been briefed by a U.S. official before his trip. Robertson stated: these operations are “not a matter for NATO”; they are an issue “between Sweden and individual countries”, and he added: “If retired secretaries of defense [like Caspar Weinberger] want to sound off that is their prerogative”. All of these top officials spoke about U.S. and UK forces testing of Swedish and allied coastal defenses after Navy-to-Navy consultations. These were state-to-state operations, not NATO operations, because they were too sensitive to be run within the multilateral framework of NATO. The risk of having a leak was too obvious. Even as the top leader of the NATO Military Committee, General Eide was not briefed by the Americans and the British on sensitive matters, he said. More sensitive information, he said, he had received from the Chief of Norwegian Military Intelligence Service Alf Roar Berg. NATO as an organization was denied essential information. Eide was better informed as a Chief of Defense of Norway (1987-89) than he had been as top leader of NATO, he said.

All U.S. and British submarine activities in the Eastern Atlantic, including the Barents, the Norwegian Sea and the Baltic Sea, were coordinated by a NATO command, by the British COMSUBEASTLANT (Commander Submarines Eastern Atlantic) in Northwood outside London and by his U.S. Deputy, but sensitive operations like the Swedish ones were run by national commands, by commanders of individual states, in Britain most likely by Flag Officer Submarines (FOSM), who actually was the same officer as COMSUBEASTLANT but with a “national hat”. In addition, two secret NATO committees responsible for the Stay Behinds also ran secret submarine operations into Scandinavian waters, the Clandestine Planning Committee (CPC) chaired by SACEUR himself (Supreme Allied Commander Europe General Bernard Rogers), and the Allied Clandestine Committee (ACC), which had rotating chairmanship. The latter also included the neutrals like Sweden, Wolbert Smidt former BND Director Operative Intelligence, told at an intelligence conference in Oslo in April-May 2005 and at his home in Berlin the following year. He had been German representative to both these committees. The latter was the only Allied committee, which had a Swedish representative, he said. However, the provocative operations with submarines showing periscopes and sails from 1982 onwards were not the ACC-CPC operations. The operations in Swedish naval bases and harbors in the 1980s were not run by these committees, he said. These provocative tests (or deception operations) were, as General Eide said, too sensitive operations to be run within the framework of NATO. However, national US and British tests or deception operations as described by Caspar Weinberger, John Lehman, and Keith Speed above and by top-CIA and Navy representatives below could profit from the restrictions on the use of force developed for the submarines under ACC-CPC command. These latter submarines were not supposed to be visible on the surface.

But why did Caspar Weinberger speak about this very sensitive “testing” of Swedish and others’ coastal defenses, “the most secret thing we have”? to quote a senior White House official. A former Chief of U.S. Naval Intelligence Europe wrote: “I wonder why he [Weinberger] let himself get into such a discussion; he should have avoided it (my opinion)”. However, already in the 1990s, I spoke to a former assistant to the Secretary of Navy and assistant to the Chief of Naval Intelligence. I told him about the evidence I had. The responsible people on the U.S. side knew already then that the information about the U.S. and British operations in Swedish waters would be made public. They were afraid of a “backlash”. They perhaps thought that their best option was to describe the operations in Swedish waters as a “regular testing” of the coastal defenses similar to how you test your military forces or “test a weapon”, as Weinberger said. He tried to make the intrusions into something banal, but the Swedes were not willing to buy that explanation. It certainly was something more. The “Deception Committee” as well as the CIA and the Navy profited from this “testing” to use it for deception purposes. This deception was an ideal instrument “to tweak the Soviet paranoia”, to quote Secretary Lehman, but it was also ideal to change Swedish politics. Lehman said that the Soviets would conclude: “Wow, if they [the US] are doing that [running operations in Swedish waters], what else might they be doing – making them feel vulnerable”. The interview with Weinberger forced Swedish Prime Minister Göran Persson to appoint Ambassador Rolf Ekéus to head an inquiry to investigate foreign intrusions into Swedish waters. As his Secretary General, he recruited Ambassador Mathias Mossberg. I was recruited as a civilian expert to this inquiry.

This article is, as I wrote in the introductory remark, largely a translation of my chapter 3 in my Swedish book "Det svenska ubåtskriget" (Medströms, 2019). However, compared to the chapter, I have also added some changes and corrections. In the book, I wrote that National Underwater Reconnaissance Office (NURO) probably played a significant role for running these operations. This had been implied by several senior actors including a senior White House official and a CIA Deputy Director for Intelligence, which I also discuss in Part II of this article. However, after my conversation with Admiral Bobby Inman in 2021, I had to modify this statement. I am now convinced that the order hierarchy from DCI Casey down to the operations in Sweden did not pass through Naval Intelligence and NURO but went directly to Admiral Lyons and to his PSYOP and deception staff. The Swedish operations were rather run by what Norman Channell (at the Naval Postgraduate School) described as "the Agency crowd and the SOF people", but that will become clear in the second part of this article.

Thanks, Ola

Hej Ola, very interesting all this. But what about the "Soviet Whiskey-class submarine S-363". It did appear in the Stockholm archipelago, didn't it? But you don't mention a word about it in this article. Thx.